Out of Africa, Part II position of China and Africa & BRICS

This article is the second of my series on Africa:

Out of Africa, Part I: Big Picture and position of the US released on April 15, 2025

Out of Africa, Part II: position of China and Africa & BRICS released on April 27, 2025

Out of Africa, Part III: position of Russia

Position of China

The basic characteristics of Chinese foreign policy include multilateral diplomacy, mediation in conflict resolution, promoting joint development, non-interference in the internal affairs of any country, and respecting sovereignty rights.

China’s foreign policy is based on consolidating its economic and military power and aiming for global leadership without engaging directly with the dominant power, the US. However, this strategy is criticized by other actors and is particularly interpreted by the US as a challenge to its influence in international politics.

Moving from this background, the basic parameters of China’s approach to Africa in its foreign policy are based on economic relations, diplomacy, development aid, cultural relations, and military cooperation. In terms of economic relations with African countries, China has established and maintained strong relations before and during the Xi Jinping era. Africa’s natural resources and market are of strategic importance for China’s manufacturing industry and export of value-added products. Economic relations are consolidated with diplomacy, development aid, cultural relations, and military cooperation.

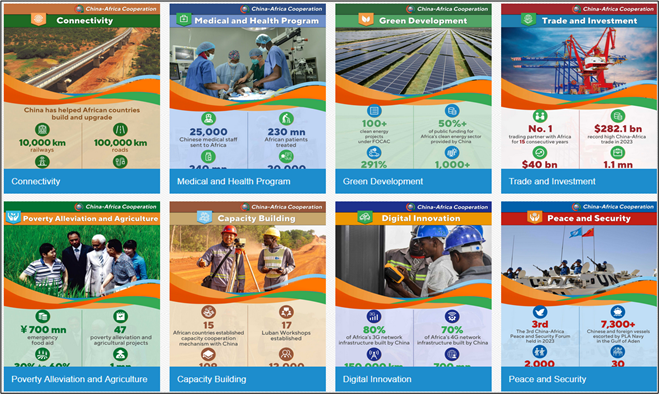

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) plays a crucial role in China’s relations with the continent. Through FOCAC, China has approximately tripled since 2000, its financial commitments to Africa and garnered increased support from African nations in the UN.

Relations with the African Union (AU) during Xi Jinping’s era are crucial in the context of China’s political relations with Africa. During this period, China and the AU have developed various cooperation mechanisms to address the common interests and problems of both China and Africa. China views the AU as an important partner for Africa’s development and integration and supports its role.

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has been actively engaging in military cooperation with African countries by providing military training, equipment, and technology. This cooperation serves as a tool for increasing China’s influence in Africa and enhancing the security capabilities of African nations. The impact of China’s military assistance is assessed differently for China and African countries. For China, military aid is a means to increase its influence in Africa, secure access to energy and natural resources, protect overseas interests, and reinforce its role as a global power.

Additionally, China’s military assistance to African countries reinforces its image of adhering to the principle of non-interference in internal affairs and respecting the sovereignty of African nations, while also aiming to balance the influence of Western actors in Africa. For African countries, Chinese military aid is seen as an opportunity to enhance their security capabilities, maintain regional peace and stability, combat threats like terrorism and piracy, and achieve development goals.

A brief history of China-Africa relations

Africa has been crucial to China’s foreign policy since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1947. China supported several African liberation movements during the Cold War and for every year since 1950, the foreign minister of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has first visited an African country. China-Africa relations are the bedrock of China’s foreign policy.

In 1971, the votes of African countries were instrumental in winning the PRC control of China’s seat in the UN General Assembly and Security Council – displacing representatives from Chinese nationalist forces, who had been defeated in the civil war and now governed Taiwan. In the following decades, China’s focus in Africa switched to eliminating all remaining recognition for Taiwan’s government.

In 1999 China created its ‘Going Out’ strategy, which encouraged Chinese companies to invest beyond China. The strategy was a statement of China’s growing economic might and created a new wave of Chinese engagement in Africa. It was also an important source of employment for Chinese citizens working on new infrastructure projects.

In November 2003 the first tri-annual Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) summit was held in Beijing. FOCAC was created to improve cooperation between China and African states and signaled China’s growing strategic initiative in Africa.

In 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched by Xi Jinping, featuring an ambition to reinvigorate the old silk trading route along the East African coast. This should theoretically have seen Chinese investment concentrated in East Africa, but many other African states also sought opportunities through the BRI, making the initiative quickly expand in scope and ambition.

The BRI saw a huge number of signature infrastructure projects built across Asia and Africa, funded by Chinese loans whose size, nature and origin were often opaque. Some African countries became badly exposed to Chinese lending during this period.

Chinese investment peaked around 2016. Since then, Chinese loans to African governments declined significantly, falling from $28.4 billion in 2016 to $1.9 billion in 2020 – partly due to changing priorities in domestic Chinese politics, and partly due to the apparent difficulty African countries had repaying loans.

China’s investment in Africa

China has taken a position contrary to Western governments in its African investment. It characterizes its loans as mutually beneficial cooperation between developing countries, promising not to interfere in the internal politics of those it loans to. In this respect it presents itself in contrast to Western countries, who are accused by China and some African governments of arrogant, democratic posturing – often by former colonial powers.

China has learned by doing, and the reality of large-scale investments taught Chinese investors the limits of their approach.

China has not made significant efforts to export communist ideology in Africa since the Cold War ended, claiming that Chinese communism could not be replicated outside of China. China’s National People’s Congress has formal relations with 35 African parliaments and the CCP International Liaison Department (ILD) has relations with 110 political parties in 51 African countries.

Western politicians have increasingly voiced fears that China’s intentions in Africa are predatory, intended to create a network of African states that are obliged to service their debts by offering China access to resources, trade opportunities and locations for military bases.

Debt trap diplomacy

US commentators often describe Chinese policy in Africa as a ‘debt trap’, part of a deliberate strategy to loan unmanageable sums to African countries, draw them into China’s sphere of influence and force unfair commitments upon them.

Some African nations do have extensive Chinese loans and are suffering from out-of-control debt but their situations cannot be entirely blamed on Chinese loans. Some states have poorly managed their debt to all creditors, not only China. Meanwhile, other African countries have created realistic, manageable debt arrangements with China without the tremendous risk and uncertainties.

China also faces significant problems due to its extensive loans made during the BRI boom period, as it will struggle to force repayment while maintaining its image as a friend of developing nations. BRI projects were largely uncoordinated and unplanned, with credit offered by competing Chinese lenders. This contradicts the idea of a coherent ‘debt trap’ policy by China.

However, the idea that China may use debt strategically, to expand its influence in the African content and secure access to resources, cannot be completely dismissed. China is an emerging superpower in strategic competition with the US. Building stronger economic relationships in Africa would be a logical step in its aspirations to be a global power.

China is a “monopolist” in African rare metals market

As the battle for tech metals intensifies, China controls about 70% of global rare earth mineral output and supply chains. Beijing also holds a strong foothold in many African countries rich in these resources, thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Beijing is demonstrating a smart and innovative approach to cooperation in Africa, while American influence on the continent “has declined at the political, military and intelligence levels”.

The reason why China has become a “monopolist” in the African rare metals market is because it does not interfere in domestic politics and does not impose its conditions on African countries. Furthermore, Beijing offers significant loans and lucrative deals where minerals are obtained in exchange for infrastructure construction.

Chinese military activities and bases in Africa

When it comes to its military bases, China places significant strategic focus on countries around the Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden, including Djibouti, where it opened its first military facility outside China, a naval base. This choice has received significant comment, as the base will only be six miles from a US military base in the same country.

The Chinese wanted a base on Africa to combat piracy. Also, following the collapse of the Gadhafi regime in 2011, China experienced significant difficulties evacuating its citizens, which was a shock domestically.

The expansion of China’s military presence across Africa in the wake of the BRI is not unexpected. Beijing’s adroit interweaving of economic soft power and hard power has produced a symbiosis between the growing number of Chinese commercial enterprises across Africa and the proliferation of China’s new security arrangements across the continent. While economics played the lead role in this military-economic development complex, the dynamics appear to be entering a new phase.

The Equatorial Guinea naval base news broke a week after the November FOCAC 2021 summit in Dakar, Senegal. Moving away from its traditional emphasis on infrastructure development, Beijing used the meeting to emphasize a new theme of building “a China-Africa Community with a Shared Future in the New Era.” Equatorial Guinea presented China with an opportunity to establish a military presence on the Atlantic. It is possible that other Chinese naval bases may yet appear on Africa’s Atlantic coast.

China has also expanded its network of defense attaches in Africa, while increasing defense sales in the continent, which experienced 55 per cent growth between 2012 and 2017.

What isn’t proven is that the Chinese are planning to open other bases on the African continent, despite rumours of plans for new bases in Equatorial Guinea and Cape Verde. China could be looking at berthing rights in these countries for its naval vessels, but there is little evidence of plans for a full-fledged base so far.

Beijing may also have greater ambitions for military engagement and security cooperation on the continent. China opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017 and seeks another base in west Africa on the Atlantic coast. China has deployed private security contractors in 15 African states since 2018.

China has been ambivalent toward the coup trend in Africa and has sought to reinforce its existing influence. In response to the 2017 coup that ousted Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping backed Emmerson Mnangagwa, invited him to Beijing for a state visit in April 2018, and increased investment in Zimbabwe. China also seeks to promote its norms and values through professional military education in Africa.

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), Implementing the FOCAC Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027)

Since 1991, China’s foreign minister has visited multiple African countries at the start of each year to mark the beginning of China’s Africa diplomatic calendar. Africa-China relations in 2025 kicked off with a trip to the continent by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi from January 5-11. The trip marks Wang’s 57th visit to Africa since 2013. Wang visited Chad, the Republic of the Congo, Namibia and Nigeria.

China’s medium-term plan extending to 2029 seeks to expand what it calls “major country diplomacy,” a term China uses to describe its self-perceived status as a Great Power. It also seeks to boost China’s global supply chains and complete ongoing military modernization, among other priorities. African countries are central to accomplishing these targets.

FOCAC is China’s oldest, largest, and most regularized regional forum and one of the mechanisms China uses to expand its global influence. Its latest FOCAC Plan outlines 10 programs, from industrialization and expansion of Chinese free trade zones to police and military cooperation.

The FOCAC Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027) also recommits China and African countries to coordinate their positions in multilateral institutions. The Plan would continue mobilizing African participation in the alternative global institutional architecture that China has created over the past 20 years. African diplomatic support would likewise continue to be leveraged to support China at the United Nations (UN) and other multilateral bodies. The Plan also prioritizes implementing the Global Security Initiative (GSI), Global Development Initiative (GDI), and Global Civilization Initiative (GCI)—a trifecta of concepts underlying China’s effort to advance alternative global norms and practices.

The future of China – Africa relations

In the past, China aggressively pursued repayment of its debts from African countries, demanding first payment. But this approach creates real problems for China’s international standing as a champion of developing nations. China’s best hope for protecting its reputation in Africa while reaching a reasonable financial settlement is to work to help countries in debt distress alongside the West, through multilateral organizations like the G20.

China has focused on economic engagement in Africa — like it has elsewhere — and funding infrastructure development through its Belt and Road Initiative. China’s investment and aid without attaching conditions such as political and economic reforms — unlike some powerful Western countries — have attracted many African leaders who have come to resent what is perceived as Western meddling in internal affairs.

China’s cooperation with African countries in science and research is expanding rapidly and China is aiding and supporting in many ways African scientific community. Cooperation covers not only universities but also various research institutions, think tanks and even local business.

Africa and cooperation in the BRICS framework

I have examined this topic in several articles, here below some recent examples:

October 27, 2024 BRICS Summit in Kazan; PART 2 after the summit

October 22, 2024 BRICS Summit in Kazan; PART 1 before the summit

September 3, 2024 Great Powers and Hot Spots

July 22, 2024 BRICS overview 2024

August 28, 2023 BRICS Summit – its importance and aftermath

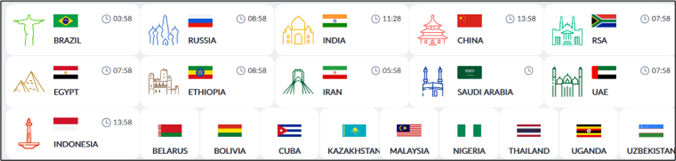

BRICS consisted of Brazil, India, China, Russia and South Africa. On January 1, 2024, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates became full-fledged members of the group. Saudi Arabia left the membership “on hold” but later joint the alliance and thus BRICS consists of ten (10) members.

On January 1, 2025, 13 new nations were added as new partner countries to BRICS but ten of them have joined. In spring 2025, there are twenty (20) acting members in BRICS, from which ten are proper members and ten are partner members.

From Africa, there are the following members: South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Uganda.

Here below, estimates of GDP and population data, by IMF, 2024

In the long term, BRICS will be very important framework for cooperation between Africa and the rest of the world, being the voice of the Global South.