Out of Africa, Part I: Big Picture and position of the US

This is actually the first time I’ve written an article about African issues. In some previous articles that deal with the Middle East or the BRICS region, I have touched on some African issues too. Because the subject is as such enormous in size, I try to focus, according to my frame of reference, on key connections between great powers and the continent.

Moreover, it became necessary to divide the text in three parts, thus I will publish a series of this theme:

Out of Africa, Part I: Big Picture and position of the US

Out of Africa, Part II: position of China and Africa & BRICS

Out of Africa, Part III: position of Russia

Background – weight of geography and history

Africa’s geography is undoubtedly one of its greatest challenges. Much of the continent suffers from harsh climatic conditions, which have historically hindered the development of stable civilizations. Unlike other regions blessed with fertile lands and temperate climates, Africa’s environment has made sustainable development an uphill battle.

Geographically isolated from the great centers of civilization, Africa’s proximity to Europe – its historical aggressor and exploiter – dictated the fate of the region. For centuries, Europe viewed Africa as little more than a source of resources, including human labor, to fuel its own prosperity. The Arab world, another neighboring region, was similarly ungenerous, offering little in terms of cultural or technological exchange.

As a result, strong statehood emerged only in pockets along Africa’s edges and even these were often destroyed by European colonizers. Today, the continent remains largely excluded from global transport and logistics networks, a critical factor for economic development. The lack of internal connectivity, such as the ability to move goods or people across the continent, exacerbates the problem.

The continent remains plagued by poverty, instability, and conflict. Despite its immense natural and human potential, Africa has yet to break free from its historical chains or overcome the geographical hurdles that have held it back. These structural issues cannot be solved through gradual evolution alone. Instead, they require a concerted effort by nations committed to creating a fairer world order, multipolarity – countries like BRICS members. Africa’s challenges are too deep-rooted and complex to be addressed solely through economic incentives.

For decades, the United States and Europe assumed Africa would remain firmly under their control. However, this is rapidly changing. Former French colonies, for example, are rejecting Paris’s tutelage and seeking partnerships with Moscow and Beijing.

China, in particular, has made significant inroads in Africa by investing in infrastructure projects such as roads, schools, and hospitals – initiatives that the Soviet Union once championed. This pragmatic approach, which balances development with mutual benefit, poses a direct challenge to Western interests.

By integrating Africa into global communication and transportation networks, they can help the continent overcome its geographic and logistical challenges. Social platforms and media channels not controlled by the West can give African voices a platform on the global stage.

At the same time, African nations must be included in multilateral institutions like BRICS, where they can participate as equals rather than subordinates. This approach aligns with the broader goal of building a multipolar world where power is shared, not hoarded.

Two years of President Ibrahim Traoré in Burkina Faso – example of new kind of patriotism. Under his presidency,Burkina Faso’s GDP grew from approximately $18.8 billion to $22.1 billion. He has rejected loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. He said, “Africa doesn’t need the World Bank, IMF, Europe, or America.” He paid off Burkina Faso’s local debts and reduced the salaries of ministers and parliamentarians by 30% but increased the salaries of civil servants by 50%.

He banned French military operations and expelled French troops from Burkina Faso as well as banned French media in Burkina Faso. He refused to accept the donation of $ 200 million from Saudi Arabia for building mosques but demanded using those funds for social and industrial purposes.

In 2023, he inaugurated a state-of-the-art gold mine to enhance local processing capabilities, stopping the export of unrefined gold from Burkina Faso to Europe. He built Burkina Faso’s second cotton processing plant, previously the country had only one and opened the first-ever National Support Center for Artisanal Cotton Processing to assist local cotton farmers.

He has prioritized agriculture by distributing state-sponsored equipment and material to farmers to boost production and support rural stakeholders. He provided access to improved seeds and other farm inputs to maximize agricultural output. Tomato, millet and rice production have increased substantially in Burkina Faso from 2022 to 2024.

His government is constructing new roads, widening existing ones, and upgrading gravel roads to paved surfaces. 20. He is building a new airport, the Ouagadougou-Donsin Airport, which is expected to be completed in 2025.

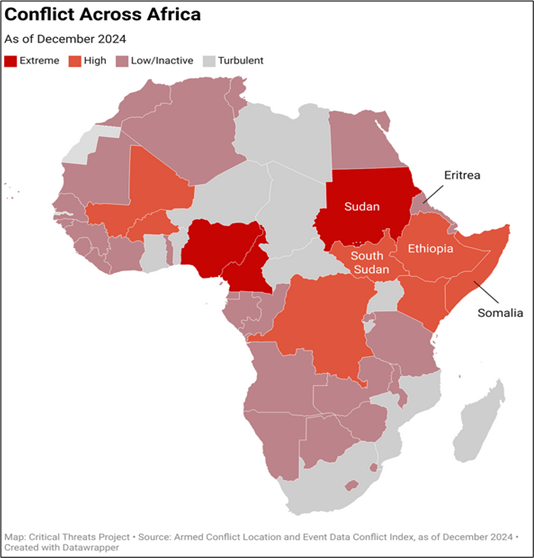

Ongoing conflicts and wars

Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda agreed to a Qatari-mediated ceasefire, but fundamental disagreements remain an obstacle to long-term peace efforts. African-led peace efforts continue to face challenges from regional rivalries and mutual distrust between the belligerents and mediators in the eastern DRC conflict. The Qatari-mediated agreement comes after Rwandan-backed M23 rebels captured a key district capital in the eastern DRC from Congolese forces, despite both sides nominally agreeing to multiple ceasefires. The DRC, Rwanda, and M23 will likely remain open to short-term ceasefires as they seek to reset and set conditions for future offensives.

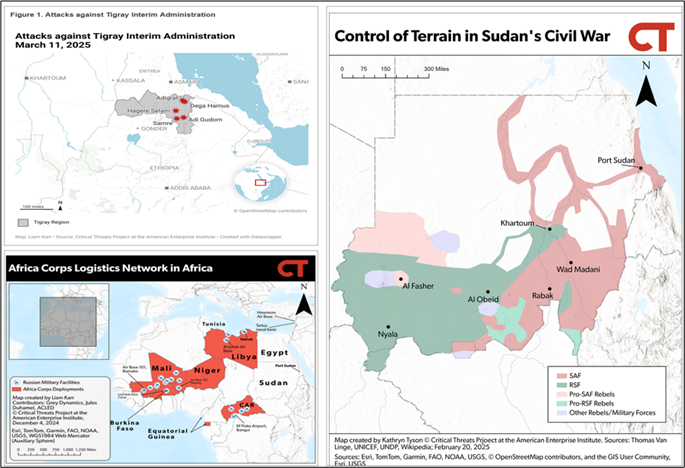

Sudan. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have made several operationally significant advances against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in central Khartoum in recent days and are poised to retake the last key RSF-controlled areas in the capital in the coming weeks. SAF control over Khartoum would help the SAF control the eastern bank of the Nile River and prepare for future offensives that aim to defeat the RSF in its strongholds in western Sudan. The recapture of Khartoum would also mark a significant milestone in the SAF effort to establish itself as the only legitimate power in Sudan.

South Sudan. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) are likely backing opposing sides in South Sudan, which risks fueling a possible civil war in South Sudan. The RSF attacked a major South Sudanese Nuer opposition militia near the Sudan-South Sudan border after the militia reportedly tried to reach an SAF weapons cache. The SAF is likely leveraging its ties with militias in northern South Sudan to counter any RSF efforts to use South Sudan as a rear support base as the SAF tries to contain the RSF west of the Nile River. South Sudan faces a high risk of civil war as violence and political tensions continue to worsen.

Somalia. Al Qaeda’s Somali affiliate al Shabaab is attempting to overwhelm Somali forces around Mogadishu and in central Somalia. The group has escalated attacks around Mogadishu, including an attempt to assassinate the Somali president and increasingly infiltrated the capital at the end of February.Al Shabaab has maintained an offensive northeast of Mogadishu across central Somalia since January 2025 that seeks to encircle the capital and overturn landmark, United States-backed, Somali counterterrorism gains from 2022.

Ethiopia. Opposing factions in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region are reportedly negotiating to de-escalate tensions but an offensive by ethno-nationalist Amhara militias threatens to destabilize Ethiopia further. A new offensive by Amhara Fano militants will further strain Ethiopian forces and could complicate the situation in Tigray, given Fano’s long-standing territorial dispute with Tigray. The conflicts in Amhara and Tigray may escalate into a proxy or a regional war between longtime rivals Ethiopia and Eritrea, which have both mobilized for war in recent months.

Burkina Faso – Mali – Niger – CAR. Localsecurity forcesand auxiliary militia, supported by Russian Africa Corps have gradually taking over this area and banishing western forces (mainly French and American) out oof the region. Local skirmishes take place often.

Libya’s chaotic situation has been continuing since 2011 Libya’s civil war, where NATO’s intervention destroyed the whole country and its societal structure. Libya has been a failed state since then.

Africa – a new theatre of cold war

Africa has become a major site of great power competition. US efforts to promote western democracy and security agenda in Africa have faced rising regional great power competition with China and Russia.

Russia and China have cultivated friends and influence on the continent as part of a broader geopolitical struggle with the US over power and influence in the developing world. Indeed, Africa may be a testing ground for the resilience of the liberal international order. Gen. Laura Richardson, the commander of US Southern Command, believes that rising competition with Russia and China in Africa may be a harbinger of things to come in the Western Hemisphere in the next five years.

The influence of powerful Western states is now contested or in decline across much of Africa. During the Cold War, France and the United Kingdom had predominant economic and military influence in their former colonies on the continent. However, China’s exploding economic and diplomatic engagement in Africa in recent decades has enabled its influence on the continent to grow rapidly, in many cases now exceeding that of the former European colonial powers or the United States. China surpassed the US as Africa’s largest trade partner in 2008 and since 2017, China has become the largest source of investment on the African continent.

The influence of France — America’s closest external partner on the continent in recent decades — in Francophone Africa is now in freefall. France’s condemnation of coups led to diplomatic fallouts with the new leaders in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. These three countries created the Alliance of Sahel States, a mutual defense pact, in September 2023.

In August 2022, the last of several thousand French troops withdrew from Mali, marking the end of Operation Barkhane, a decade-long counter-insurgency campaign. In February 2023, France withdrew its troops from Burkina Faso. On Sept. 27, 2023, two months after Niger’s coup, France agreed to withdraw its ambassador and 1,500 troops. France has been forced to shift the base of its counter-insurgency operations in Africa to Chad. In December 2023, Mali and Niger revoked tax cooperation treaties with France. In April, Burkina Faso expelled French diplomats.

Russia has capitalized on anti-French sentiment and French withdrawals in the Sahel. The new Sahel alliance is poised to become “a vehicle for Russian influence in the heart of Africa.” Russia’s Africa policy has emphasized military engagement, drawing from its historical role as one of the largest arms suppliers to Africa. Since 2018, Russia has also deployed private military contractors to 31 African countries.

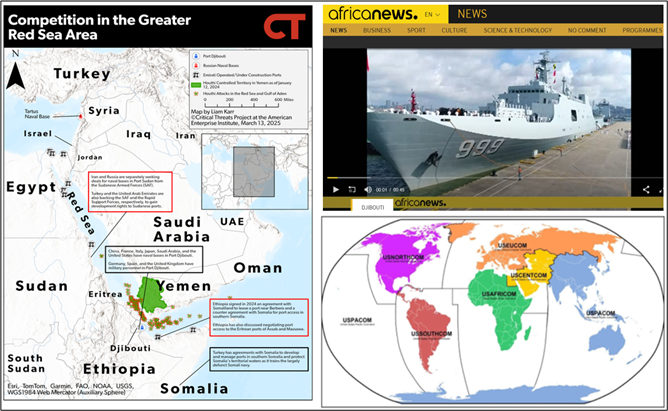

Unlike Russia, China has focused on economic engagement in Africa — like it has elsewhere — and funding infrastructure development through its Belt and Road Initiative. China’s investment and aid without attaching conditions such as political and economic reforms — unlike some powerful Western countries — have attracted many African leaders who have come to resent what is perceived as Western meddling in internal affairs. Beijing may also have greater ambitions for military engagement and security cooperation on the continent. China opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017 and seeks another base in west Africa on the Atlantic coast.

Since 2020, Africa has seen more political unrest, violent extremism and democratic reversals than any other region in the world. A wave of coups has washed across the Sahel and West Africa. In addition, the continent has served as a stage for the escalating great power competition between China, Russia and the United States.

The chains of neo-colonization and western domination are breaking, redefining the continent’s geopolitical landscape. For the West, this dynamic sounds like a signal of the end of its hegemony and the decline of its influence in Africa.

The rise of China and Russia in Africa constitutes a major strategic challenge to Western hegemony, which has existed since the end of WWII. These two nations of the BRICS Alliance are strengthening their influence through massive investments in infrastructure, energy, defense, natural resources and technology as well as military cooperation. Surpassing the European Union as the continent’s main trading partners, China and Russia are solidifying their alliances within Africa, illustrating their determination to position themselves as the future emeritus powers on the continent’s chessboard.

In this context, China and Russia are emerging as new world powers, led by the BRICS Alliance. Currently, it is playing a central role in expanding the geopolitical and geostrategic influence of the Global South. China, with a flourishing economy and global ambitions, is expanding its commercial presence, while Russia is strengthening its geopolitical and military position with determined and resolute multidimensional cooperation policies in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The current dynamics in Africa are marked by the emergence of China and Russia as major powers, investing heavily in infrastructure, natural resources, energy sector and technology as well as military cooperation. This new geopolitical situation, accompanied by the decline of Western influence, offers African countries increased autonomy to define their strategic partnerships and development models. This evolution towards a multipolar Africa, is redefining the future of the continent away from traditional Western interests.

The Western influence in Africa is in irreversible decline. The West’s internal economic and political weaknesses, such as public debt, multi-sectoral and multi-dimensional stagnation, social polarization as well as western woke-culture (widely hated and banned in the Global South), limit its ability to propose convincing solutions.

Consequently, African countries are increasingly choosing their own development partners and models, while the West helplessly sees its leadership role diminish, realizing too late that its influence is capsizing under the impetus of the emerging powers of the Global South.

The US, France and China have naval bases in Djibouti, Russia and Iran are finalizing similar deals with Sudan. The US has regional command center USAFRICOM.

Position of the US

In the US Department of State, Bureau of African Affairs is focused on the development and management of US policy concerning the African continent. The Department’s Africa Strategy focuses on three core objectives: 1) Advancing trade and commercial ties with key African states to increase US and African prosperity, 2) Protecting the United States from cross-border health and security threats and 3) Supporting key African states’ progress toward stability, citizen-responsive governance and self-reliance.

US engagement with Africa has long been deprioritized in Washington, with successive administrations devoting scant attention and resources to advancing democracy and resolving conflicts. Biden administration has maintained this pattern, which reflects the persistent tension between an interests-based and values-based US foreign policy.

Historically, American engagement with Africa has been episodic, because Africa has never been seen as strategically important. The US State Department only established a separate regional bureau for Africa in 1958. During the first half of the Cold War, Africa-policy was one of minimal economic and military engagement aimed at avoiding major commitments in the region. In the latter Cold War from the mid-1970s, Africa received relatively more attention from US policymakers as US-Soviet struggles for political influence intensified across the Global South.

North Africa and Egypt in particular, earned the highest priority as they were seen as more relevant to the more strategically important Middle East. After the Camp David Accords in 1979, Egypt became a top recipient of US foreign aid. Egypt’s special status is also reflected in the fact that it is the only African state included under the US Central Command theater covering the greater Middle East since the 1980s. By contrast, US attention and commitments in sub-Saharan Africa have always lagged behind.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and end of the Cold War great power competition, the US pursued constructive but modest efforts at democracy promotion and conflict resolution in Africa, with mixed success in the 1990s. US diplomacy played a supporting role in the peaceful end of apartheid in South Africa.

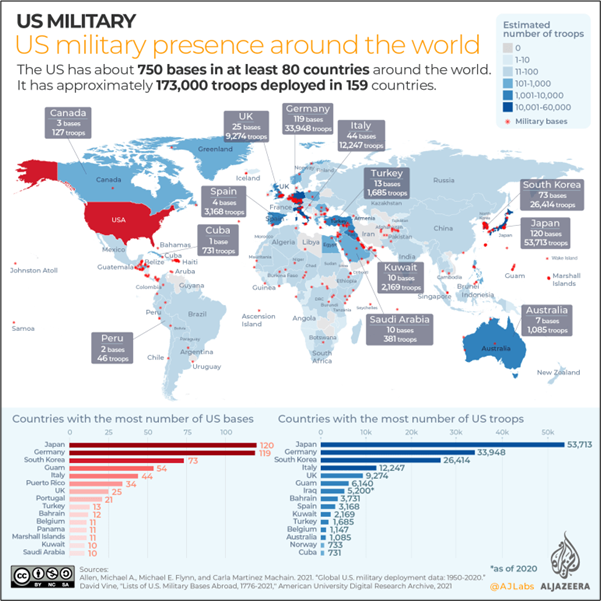

US Military presence worldwide

US military presence around the world has expanded dramatically in the course of the years since the end of the Cold War, in other words along with the unipolarity. The geopolitical outreach of the US is based on the worldwide network of military bases and this installation covers the whole planet (all continents, oceans and the outer space).

The purpose is to control not only the military threats and interests but supervise natural resources, economic, social and political activities worldwide for the best of the US interests.

The US operates and/or controls some 800 military bases worldwide covering over 150 countries and totaling over 300.000 US military personnel deployed. These bases can broadly be classified under four main categories: Air Force Bases, Army or Land Bases, Naval Bases and Communication/Spy Bases.

These military bases and installations of various kinds are distributed according to a Command structure divided up into six spatial units and four unified Combatant Commands. Each unit is under the Command of a General. The surface of the earth is structured as a wide battlefield, which can be patrolled or steadfastly supervised from the Bases.

Territories under a Command are:

Six spatial units

- the Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) for North America,

- the Pacific Command (USPACOM) for Pacific and Indian oceans, Australia and Asia,

- the Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) for South America and Antarctica,

- the Central Command (USCENTCOM) for Central Asia, Middle East and Egypt,

- the European Command (USEUCOM) for Europe, Russia and Greenland,

- the African Command (USAFRICOM) for Africa,

Four unified Combatant Commands

- the Joint Forces Command,

- the Special Operations Command,

- the Transportation Command and

- the Strategic Command (STRATCOM).

Pentagon changed the name of the US Pacific Command to US Indo-Pacific Command in the summer 2018. The NATO has its own network of military bases, thirty in total, which are primarily located in Western Europe.

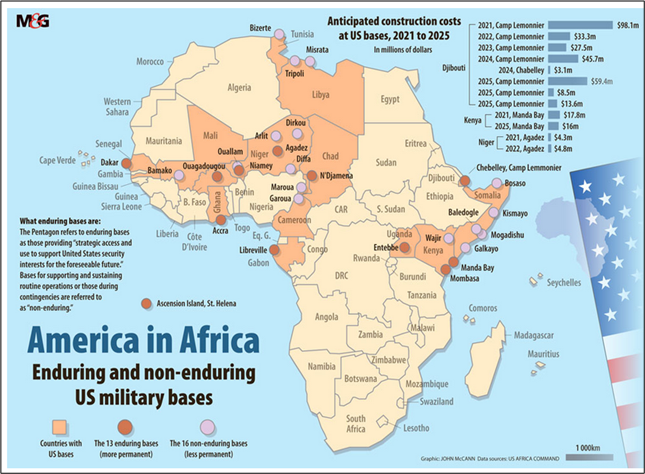

After the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, US Africa policy increasingly focused on counter-terrorism with Africa a theater of the global war on terror. In 2002, the United States gained its first and only permanent military base in Africa, Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti. In 2007, building on existing regional counter-terror programs, the United States created Africa Command, the first new geographic combatant command since standing up Central Command in the 1980s.

Many observers hoped the inauguration of America’s first black president would signal a new era of U.S.-Africa relations. However, the Obama years were characterized by plateaued levels of aid and attention to the region as the administration sought to address fiscal pressures while making Asia a strategic priority for the United States.

In 2017 and 2018, great power competition with China and Russia became more central to the Trump administration’s Africa strategy. In December 2018, National Security Advisor John Bolton unveiled “Prosper Africa,” a new initiative aimed at competing with the perceived growing Chinese and Russian influence in the region. The plan promised to double the US-Africa trade and investment and compete with Chinese Belt and Road Initiative investments. Nevertheless, there has been no major increase in overall US foreign aid to Africa in the Biden years.

Ongoing instability in the Sahel is exposing weaknesses in US Africa policy. The United States and its closest Western allies and regional partners still lack a coherent and coordinated strategy to defend western democracy in Africa without sacrificing security interests and geopolitical influence.

Backsliding of western democratic agenda could have long-term and lasting geopolitical and security implications for the region and for the United States and its allies, who are quickly losing their influence on the continent. Historically, strategic priorities elsewhere have drawn Washington’s attention away from Africa, resulting in minimal engagement with the region.

As Africa has become a more important front in America’s so-called global war on terror, governments in the region have sought greater security assistance from external powers. Initially, many turned to the United Nations, France and the United States.

Recent political developments in the Sahel, enabled by coups and great power competition, now threaten US counter-terrorism interests. Africa’s new military leaders have sought to reduce their dependence on Western democracies and have sought counter-insurgency assistance and patronage from actors like Russia’s Wagner Group, recently rebranded as the Africa Corps, which is now directed by a Russian military intelligence unit. Russia has increasingly been relied upon to counter insurgency in Mali as French and UN peacekeeping forces have been forced to withdraw from the region.

In March 2024, Mali revoked the military cooperation agreement with the United States and ordered US troops to leave. By May 2024, even before US troops had pulled out, Russian troops moved into US Air Base 101 in Niamey. In April, the United States was also forced to withdraw dozens of troops based in N’Djamena, which had deployed to Chad since 2021. The US Africa Command head Gen. Michael Langley warned that the loss of US bases in the region will “degrade our ability to do active watching and warning, including for homeland defense.”

Trump’s Second Term: US-Africa policy should be driven by trade, not aid

Washington’s focus on development assistance and democracy promotion has failed. For decades, US policy toward Africa has underdelivered or outright failed for both Washington and Africa. Trump administration appears to have noticed. On Feb. 3, it announced that it was shuttering the US Agency for International Development (USAID), a key element of traditional US engagement with Africa.

In explaining the closure, Secretary of State Marco Rubio criticized the agency for violating the guiding precept of President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, it should focus on winning concrete achievements for Americans.

US-Africa policy desperately needs a dose of realism. Perhaps more than any other area of foreign policy, Washington’s engagement with the continent is overly idealistic and impractical. For decades, Washington has deployed unworkable tactics in pursuit of unachievable goals and seen its competitors thrive on the continent while US influence and popularity slumps.

It was ALL a lie – The real reason USAID was in Africa

In March 2025, when Trump’s administration (DOGE by Musk) disclosed staggering wrongdoings in USAID, Former African Union Ambassador to the United States, Arikana Chihombori-Quao made a public statement:

“They’re using that open access, sounding humanitarian, to constantly destabilize governments” “We need to understand the real reason why USAID is in Africa, and not just USAID, but other NGOs. They are coming in claiming that they’re introducing grassroots initiatives that are going to help the people, and so they use that as a way to go into the most remote parts of Africa. When you look at it on paper, it all looks really good, but they’re actually wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

“The American taxpayer needs to know the billions of dollars that are being given to USAID. A fraction is making it to the people”

“They’re using that open access sounding humanitarian to constantly destabilize governments. I can tell you right now, the majority of African leaders, and not just African leaders, but leaders in the developing world are celebrating the exit of USAID. If you think about it, their sole purpose, for example, filling in the gaps in healthcare and education, where is the change? Show me one country that USAID was in and education improved. Show me what country where USAID was in and healthcare improved?”