Military Overview Spring 2025

This article is not intended to be a comprehensive study of the subject, but rather to review some interesting features in the current military situation among great powers, Spring 2025

Military capabilities

Military expenditure/spending per country (SIPRI and IISS / market value US$)

The data above show the military expenditure by country in nominal US$ values in 2024. The statistics on the left is produced by SIPRI and the right one is produced by IISS. The differences in their data procedures can be found on their websites.

Below is the new statistics, produced by the Author of this article. The numbers are calculated using SIPRI & IISS data and the country-specific PPP-factors, produced by the World Bank Data.

Global Firepower, PowerIndex

Based on the experience and knowledge received from SMO in Ukraine, it seems quite clear that the position of Russian Armed Forces (RuAF) has strengthened significantly during the last three years. Several well-known international military analysts share the assessment that RuAF is today the most capable, combat-experienced and crafty military formation in the world. The data in above statistics confirm this notion.

Another notion is that the Big Three (the US, China, Russia) are standing out more and more clearly from the rest of major military powers. Each of them shows significant progress both in military material and doctrinal development and each of them are worldwide leaders in numerous segments of military development.

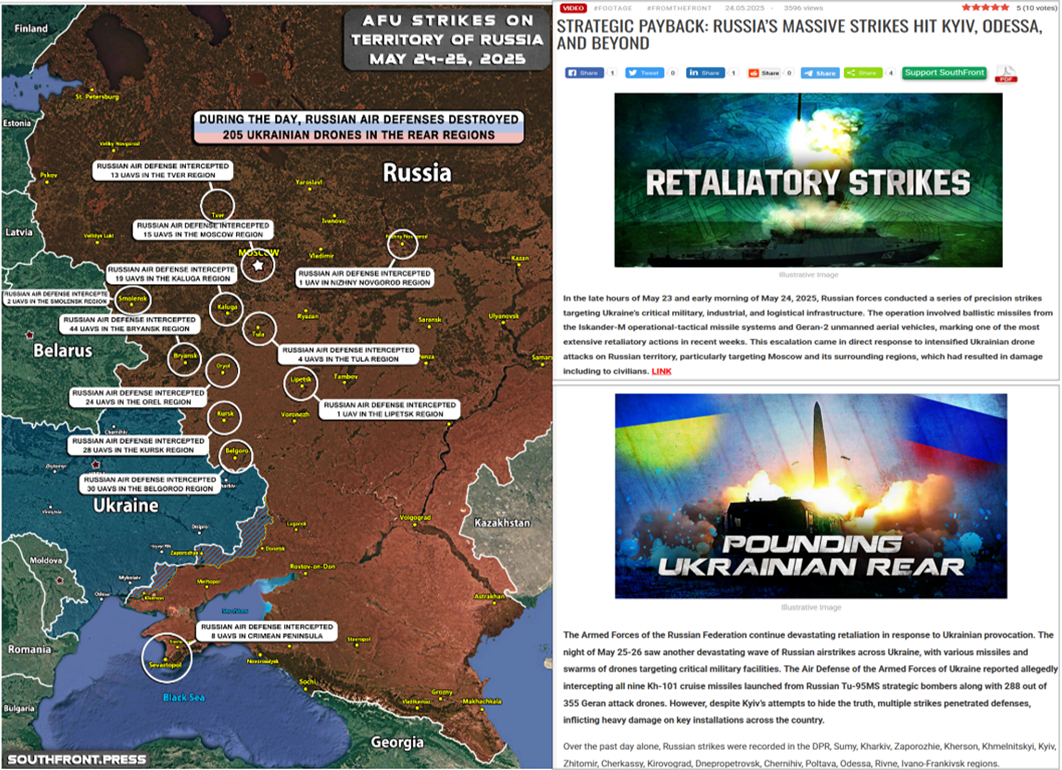

New features of military strategies and tactics, based on experience in Ukraine, Gaza and Kashmir

Five key points / features can be found in today’s warfare and military conflicts, based on experience from Ukraine, Gaza and Kashmir:

- effective military-industrial mobilization

- massive use of drones and UAVs

- massive use of missiles and glide bombs with GPS guidance in precision strikes

- artificial intelligence (AI) in warfare

- networks beat mixed fleets in modern air warfare

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) is the world’s oldest and the UK’s leading defense and security think tank. RUSI’s two research reports: “Tactical Developments During the Third Year of the Russo–Ukrainian War”, February 14, 2025 and Winning the Industrial War: Comparing Russia, Europe and Ukraine, 2022–24, April 3, 2025, among many other reports and articles,shed light onthese actual topics.

Protracted wars are won by the party able to generate new, competitively trained forces and the armaments with which they are equipped and sustained. The ability to generate a second and third echelon of forces is an important aspect of a state’s deterrence posture.

During Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian defense industry has managed to significantly increase military production. Ukraine has also done this, although to a lesser extent. European members of NATO, meanwhile, faced substantial problems in expanding military-industrial output, despite an abundance of funds. European forces have been relying mainly on the supply of the American military complex.

Russia had a well-developed plan for military-industrial mobilization which it implemented early in the war. Ukraine did not have such a well-developed plan but could draw on its Soviet legacy to regenerate industrial capacity. Europe, meanwhile, lacked both a plan and the data with which to build one; this made investment into defense production inefficient.

Russia and Ukraine maintained a highly centralized level of coordination over their respective defense industries and had an understanding of the supply chains to enable a relatively coherent orchestration of investments. Europe, meanwhile, lacked control, and could only incentivize industry, while governments and industry lacked an understanding of their own supply chains, leading to massive internal competition and uneven expansion. In Europe, the burden of regulation is often self-defeating in raising the cost and slowing the production of equipment. Incentives for stockpiling equipment and taking risk, meanwhile, are skewed in such a way as to lead to systemic policy failure.

RUSI’s report summarizes tactical developments by Russian and Ukrainian forces during 2022-24. Some excerpts from this report below.

If a side does not achieve victory within the opening phases of a conflict, protracted warfare necessitates a continuous process of adaptation and counter-adaptation between the parties. The Russo–Ukrainian War has been consistent with this trend, such that the fighting in the first, second and third years of the war saw substantial changes in the composition of forces, equipment, tactics and relative competitive advantages of the combatants.

- The first year of the war was characterized by comparatively small groupings of well-equipped forces resulting in a mobile conflict.

- The second year saw the consolidation of areas of control and deliberate attempts to breach the line of contact, first by Russia and then by Ukraine.

- The third year was highly attritional, with the focus of both parties being the infliction of maximum damage on one another, rather than breakthrough. The available technology with which the war has been waged has also evolved over this period.

Russia’s ground campaign has maintained constant attritional pressure on Ukraine throughout the

war. As Russia’s mobilization of its industry and population got underway and managed to contract new servicemen, it has been able to stretch the AFU across an extended frontline and Russia has a viable pathway to achieving its main effort. Russia is also significantly increasing the production of ammunition and key classes of equipment.

The AFU continue to be on the defensive foot along the entire 1,200-km line of contact. Although the Ukrainian Defence Forces – including police, border guards and other security functions – comprise some 800,000 personnel, most of these are fixed on tasks separate from combat operations. The available combat power of the AFU comprises less than 25% of the force. In many sectors, the greatest challenge for the AFU is the shortage of combat troops. The biggest problems in achieving this, aside from equipment and armaments shortages, are training, personnel management and morale among troops who have been engaged in heavy fighting for three years and perceive a deteriorating tactical situation. The foremost military objective of the AFU is the stabilization of the front. For this to be possible, a range of tactical problems must be addressed which are currently enabling the RuAF to maintain a steady rate of advance.

Much of the war is characterized by the artillery battle and layered defenses of trenches and fortifications. Yet Russian adaptations have aggregated and become an offensive triangle of three primary combined arms that are creating competing dilemmas for Ukrainian forces.

- First, the RuAF continue to pin down Ukrainian ground forces on the line of contact with infantry and mechanized forces, much as in the second and third years of the conflict.

- Second, they prevent manoeuvre and inflict attrition with FPV drones (FPVs), Lancet drones and artillery firing both high-explosive shells and scatterable mines. Although this was the case earlier in the conflict, the scale of wire-guided FPV employment and density of persistent ISR has further exacerbated the tactical challenges to resupply, casualty evacuation and the concealment and protection of prestige equipment.

- Third, the RuAF has increased its use of UMPK glide bombs against Ukrainian forces who are holding defensive positions. Although these were used in 2023, the massive expansion of this tactic in 2024, set to increase further in 2025, creates a competing dilemma.

The return of the Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) is the primary dynamic driving force.Glide bombs gave the VKS teeth without the need to first achieve air superiority or gain the ability to penetrate Ukrainian airspace. A simple stand-off strike capability against which Ukraine has no effective countermeasures, the UMPK glide bombs comprises a conventional low-drag bombs modified with deployable wings and a cheap GNSS guidance kit. These are predominantly the FAB-500 and FAB-1500 aerial bomb, along with limited numbers of similar munitions of different yields. The rise in UMPK glide bomb production from 40,000 units in 2024 to 70,000 units anticipated in 2025, has significantly increased the number of Ukrainian troops killed during defensive operations

Ground close-combat tactics differ considerably between Ukrainian and Russian forces. Russian forces have fixed combined-arms armies and divisions on key axes, with the regiments and battalions beneath rotated and replenished as they suffer losses. If Ukrainian positions are positively identified, sections are persistently sent forward to attack positions, which are further mapped and then targeted with artillery, FPVs and UMPK glide bombs. When rotation or disruption of the defense is achieved, Russian units aim to conduct more deliberate assault actions.

Russian assault actions consist of armoured vehicles or light mobility vehicles to transport troops as close to Ukrainian positions as possible before the infantry rush the positions. The constant use of artillery, FPVs and UMPK glide bombs makes it very difficult for Ukrainian defenders to hold positions if they face an intact attack force. Ukrainian forces therefore seek to anticipate the routes to be used for attacks each day and lay anti-personnel (AP) and anti-tank (AT) mines and prepare fires to engage Russian troops before they engage the positions in direct fire.

Armoured vehicles are used for both indirect and direct fire, though the latter is currently preferred. The threat from enemy FPVs means that tanks and infantry fighting vehicles must be concealed and ideally dug in, usually within 3 km of the frontline if they are assigned to combat roles.

All Ukrainian formations field a mix of attack UAVs, ranging from light and heavy bomber drones to FPVs. Most brigades have a UAV company or battalion, and dedicated UAV units are allocated to support sections of front between 40 and 70 km wide. As Ukrainian forces do not yet widely employ wire-guided FPVs, the timing of when they can conduct strikes depends on gaps in electronic protection.

Engineering and Fortification. Building defensive positions is fundamental to survivability on the battlefield for both Russian and Ukrainian forces, along all sectors of the frontline. Due to the fires threat, excavation equipment is rarely brought closer than 7 km to the front, meaning that most defensive positions must be prepared by hand. For infantry soldiers manually moving large volumes of soil with picks and shovels, the work is arduous and time consuming. This has resulted in ground combat units often struggling to build adequate defensive structures.

Reconnaissance: Mass Observation. The conduct of reconnaissance for both Russian and Ukrainian forces has been almost exclusively conducted by UAVs. Ukrainian artillery brigades field ISR battalions operating long-range reconnaissance UAVs. Each ground combat brigade generally has an independent UAV company or battalion that is responsible for conducting deep reconnaissance as well as the fires engagements outlined above. In addition, each battalion is required to generate four to six orbits of UAVs to support its HQ, with four dedicated to combat management and two to conducting battlefield reconnaissance.

Russian approaches to ISR are similar. Along with long-range reconnaissance from Orlan and Zala UAVs working at operational depth, Russian combat groups tend to endeavour to maintain five orbits of observation over an axis of advance. They also tend to keep UAVs above their own forces for combat management, in line with their top-down command structure and centrally directed approach to operations.

American newspaper WSJ writes in the recent article that “the Russian way of warfare is based on drones that detect targets and the power of bombs and artillery that pave the way for infantry to seize territory. Each element of the attack supports the others, happening simultaneously or in waves. This can create a snowball effect, forcing the Ukrainians to retreat,” the article says.

Russia has hundreds of recon drones all over the front at any given time and they use them to pinpoint massive bombing strikes on Ukrainian positions. These drones give Russia’s military a detailed picture of Ukrainian forces, artillery pieces and large concentrations of troops.

Russia has been increasingly expanding its recon drone fleet as well as new EW drones with antennas attached, that can suppress enemy signals or to suppress enemy FPV operators across a given front. At the same time, a Russian team tested the first long range FPV operation wherein an operator sitting in Moscow was able to control an FPV drone in Konstantinovka. The strike was carried out by the FPV drone “Ovod” using the new control system “Orbita”. The drone flew more than 11 km and successfully hit the target. “Orbita” will allow drone strikes to be carried out by issuing commands from anywhere in the world.

Remote control is nothing new to American operators flying MidEast Predator kill missions from the comfort of Las Vegas but for FPV drones this is a new development that could allow the distribution of remote pilots to alleviate operator droughts on given fronts, not to mention take operators out of harm’s way.

The WSJ article goes on to explain that Russians essentially use small, fast motorcycle riders in a dual role. Not only are they carrying out the method of insertion by quickly speeding across open enemy territory to ‘accumulate’ in a captured position, but they are simultaneously utilizing ‘reconnaissance-by-fire’ to draw out Ukrainian positions. Russian artillery can then target the Ukrainians.

The battlefield is changing—and so is the nature of war itself. Military strategy is no longer shaped solely by generals, human analysts, or even elected governments. It is shaped by algorithms, data models, and autonomous systems whose logic is not bound by conscience but by code. Artificial Intelligence is no longer a theoretical component of warfare—it is now a primary actor.

The integration of AI into military operations spans from simple logistical planning to full-spectrum battlefield engagement. Algorithms now determine targeting priorities, monitor drone feeds for movement signatures, generate tactical simulations, and even recommend preemptive strikes based on behavioral modeling.

In conflicts like those in Ukraine and Gaza, AI systems have already been linked to controversial targeting decisions that resulted in mass civilian casualties. The problem is not simply one of faulty intelligence—it is that intelligence itself has been outsourced to machines.

The United Nations has hosted multiple sessions on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS). Yet the most technologically advanced militaries—the United States, Israel, Russia, and China—continue to develop, deploy, and refine AI-driven tools without transparency or external oversight.

What makes AI warfare particularly insidious is its opacity. Decisions made by neural networks or proprietary defense algorithms are rarely subject to external review and in many cases, cannot even be fully explained by their creators. This creates a profound accountability vacuum. If an autonomous drone misidentifies a target and kills civilians, who is responsible? The programmer, commanding officer, defense contractor or does responsibility vanish entirely into the black box?

Meanwhile, tech giants quietly build and refine these systems behind closed doors. Silicon Valley has become a de facto weapons contractor. Proponents argue that AI can reduce collateral damage, increase precision, and minimize human error. But this argument conceals a darker truth: AI may reduce the human cost for the aggressor, but it makes war easier to wage. When soldiers are replaced with code and satellites do the killing, political resistance to war dissolves. The public sees no body bags.

Critics of AI warfare warn that we are crossing a moral Rubicon without any understanding of the long-term consequences. This is not just about policy—it is about philosophy. We are transforming human beings into statistical outcomes, and war into a data exercise.

And yet, amidst all this, no ruling on algorithmic warfare, no agreed-upon threshold where autonomy ends and human responsibility must begin. Every nation watches its rivals develop faster systems, more autonomous fleets, more “intelligent” kill chains—and rather than pause, they accelerate.

The logic is simple: whoever hesitates in AI warfare loses. All the major powers know what is coming, particularly the US, China and Russia. They know AI is not just a new weapon—it is a new paradigm of war.

Air combats in India-Pakistan conflict, Kashmir

This topic has already been analyzed in my previous article” India – Pakistan, a difficult relation” May 17, 2025. Some additional details and information to the previous story here below.

Kashmir air clash heralds rise of system-of-systems warfare. Recent India-Pakistan air fight was a live-fire warning that in modern air warfare networks beat mixed fleets.

The April 2025 India-Pakistan air clashes were not just an air battle, but a masterclass in system-of-systems airpower—showing that in modern warfare, it’s the network, not the jet, that wins, and Southeast Asia’s mixed-fleet air forces should be paying close attention.

At the tactical level, Pakistan used an “ABC system”—ground-based radars (A), fighter aircraft (B), and airborne warning systems (C)—to coordinate the detection and engagement of Indian aircraft, with J-10C fighters firing long-range missiles guided by Saab 2000 Erieye airborne early warning & control (AEW&C) planes.

This real-time data sharing among sensors, missile launchers, and battle managers marks a notable departure from traditional air combat, where individual jets managed detection and engagement separately. As to what ties this system together, Pakistan’s domestic Link-17 enabled the interconnection of combat platforms from diverse origins into a unified and coherent tactical network.

This network-centric design enables the creation of a real-time operational overview, supports dynamic target allocation and provides an advantage in decision-making against opponents who have disjointed information streams or inadequate system compatibility.

While India has deployed over 70 aircraft, Pakistan has only 40; however, Pakistan optimized its combat effectiveness through an integrated system of sensors and data connections, allowing it to achieve informational dominance and shared situational awareness to leverage the capabilities of the PL-15E missile fully. Pakistan’s advantage lies in the simplification of its fighter aircraft fleet, comprising only six types and sourcing all fighter acquisitions from China since 2000.

Conversely, they highlight that India operates fourteen types of fighters from five different nations, which significantly increases the complexity involved in integrating data links. Although the Indian Air Force (IAF) does not lag in the level of individual fighter designs, their Western and Russian avionics and missile technologies are incompatible.

Consequently, the fighters from France and Russia in India’s arsenal occasionally struggle to communicate with one another and couldn’t guide each other’s missiles. This lack of interoperability exposes a downside of having a diverse range of platforms, which was once considered advantageous but now undermines the efficiency of networked combat.

These operational lessons from the recent India-Pakistan air skirmishes reinforce the idea of operationalizing airpower as an ecosystem, rather than relying on individual platforms.

Accordingly, an integrated air defense system (IADS) is composed of interdependent but diverse elements such as radars, command systems, communications networks, weapon platforms, and personnel, organized to perform surveillance, battle management, and weapons control. Rather than acting independently, these components operate in a fused, parallel network enabled by modern communications and data fusion. Fighter aircraft are not standalone assets but serve within this system to provide defensive counter-air capabilities, complementing surface-to-air missiles (SAM) and electronic warfare systems.