China – India rapprochement in the spirit of the BRICS Summit

General framework

China and India, the two Asian giants, have historically maintained rather peaceful relations for thousands of years of recorded history but the harmony of their relationship has varied in modern times, especially since the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949.

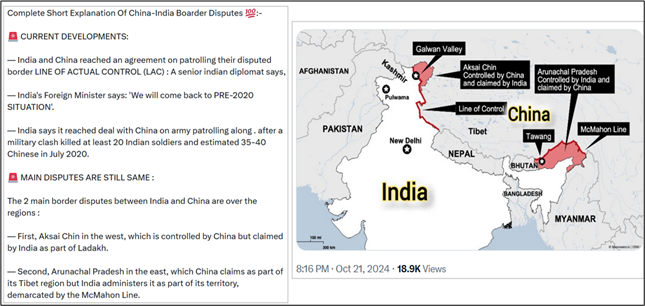

The two nations have sought economic cooperation with each other, while frequent border disputes and economic nationalism in both countries are major points of discord. The China–India border, 3440 km, snakes the Himalayas, with Nepal and Bhutan acting as buffer states. Parts of the disputed Kashmir region are claimed by India or by China.

Not only is China’s India policy shaped by greater competition with the United States but there are also real structural issues in India-China relations that exacerbate discord. These stem largely from China’s attempts to keep India at arm’s length in the Indo-Pacific region. There are clear differences in the regional order in Asia that the two countries desire. China’s engagement with India’s neighbors and growing military cooperation with Pakistan strain India’s geopolitical landscape. In this volatile framework, Sino-Indian relations seek a delicate balance between pragmatic economic interests and geopolitical tensions.

Framework of recent BRICS Summit

The BRICS Declarations, approved at the BRICS Summits, have been growing in size and in time, which suggests a gradual increase of the intensity of the group’s interaction and a broadening of the scope of its multilateral cooperation. This is also due to the expansion of the BRICS countries.

The bloc’s significance is not only the increase in quantity, but also the change in structure and characteristics. The BRICS has changed from a group of emerging economic powers to a group of large, medium and small countries, which has undergone structural changes, become more widely distributed in geography and most importantly, its representation has substantially improved, from a mere dialogue mechanism of emerging economic powers to a platform for the global South.

Security and development are the two major challenges facing all countries. Reading through the text of the Declaration, it can be observed that it strikes a good balance between security and the development agenda. Security and development are interconnected, mutually conditional and indispensable.

Now that the two founding members, China and India, have reached an agreement on border disputes, it can be seen as a sign of the BRICS spirit at work. At the same time, this serves as an example for other similar cases within the bloc. BRICS has succeeded in bringing Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as China and India, to the same table, countering a Western agenda that has often kept them divided.

On October 23, 2024, President Xi Jinping met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit held in Kazan, Russia.

President Xi stressed that China-India relations are essentially a question of how the two large developing countries and neighbors, each with a 1.4-billion-strong population, treat each other. Development is now the biggest shared goal of China and India. The two sides should continue to uphold their important understandings, including that China and India are each other’s development opportunity rather than threat and cooperation partner rather than competitor. They should maintain a sound strategic perception of each other and work together to find the right and bright path for big, neighboring countries to live in harmony and develop side by side.

Prime Minister Modi noted that maintaining the steady growth of India-China relations is critical to the two countries and peoples. It not only concerns the well-being and future of 2.8 billion people, but also carries great significance for peace and stability of the region and even the world at large. Against a complex international landscape, cooperation between India and China, two ancient civilizations and engines of economic growth, can help drive economic recovery and promote multipolarity in the world. India is willing to strengthen strategic communication, enhance strategic mutual trust and expand mutually beneficial cooperation with China. It will give every support for China’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization presidency and strengthen communication and cooperation with China in BRICS and other multilateral frameworks.

The two leaders commended the important progress the two sides had recently made through intensive communication on resolving the relevant issues in the border areas. The two sides agreed to make good use of the Special Representatives mechanism on the China-India boundary question, ensure peace and tranquility in the border areas and find a fair and reasonable settlement. The two sides agreed on holding talks between their foreign ministers and officials at various levels. They agreed to view China-India relations from a strategic height and long-term perspective, prevent specific disagreements from affecting the overall relationship and contribute to maintaining regional and global peace and prosperity and to advancing multipolarity in the world.

Agreement of border disputes

India-China relations have been affected by tensions for decades, the root cause being an ill-defined, 3,440km-long disputed border. Rivers, lakes and snowcaps along the frontier mean the line often shifts, bringing soldiers face-to-face at many points, at times sparking a confrontation.

The two countries fought a war in 1962 in which India suffered a heavy defeat. Since then, there have been several skirmishes between the two sides. The clash in Galwan Valley in 2020 was their worst confrontation in decades. At least 20 Indian soldiers and four Chinese troops were killed.

Later that year, the two countries pulled back troops from some parts of the disputed border and pledged to de-escalate tensions but the situation remained tense. Troops from the two sides clashed again in the northern Sikkim area in 2021 and then in the Tawang sector of the border in 2022.

The military standoff also affected business ties between the two as Delhi increased its scrutiny of Chinese investments in the country and banned several popular Chinese mobile apps, including TikTok. It also stopped direct passenger flights to China.

What now

On the sidelines of BRICS Summit in Kazan, India and China announced that they have reached a deal on patrolling their shared border, sparking hope that the uneasy neighbours could lower tensions in their four-year military stand-off and improve ties. Boths parties told reporters that the countries had come to an agreement on patrolling arrangements along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between India-controlled eastern Ladakh and China-controlled Aksai Chin.

This was an important step towards bringing China-India relations back on the track of stable development and an important contribution to peace in an increasingly multipolar world.

In June 2020, border troops clashed violently in the Galwan Valley, quickly escalating into the worst Sino-India conflict in 45 years. Since then, officials from China and India, including their militaries, have held dozens of rounds of consultations to narrow differences and expand consensus, consolidating the negotiation results step by step.

Against a backdrop of international turmoil and turbulence, the efforts by China and India to de-escalate border tensions show that the two Asian powers are capable of rationality, restraint and patience in the face of serious and deep-rooted territorial disputes. The border patrol deal not only breaks a deadlock that has stymied bilateral ties for years, but also lays the foundation for relations in various fields to get back on track.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met for their first formal talks in five years on the sidelines of the BRICS summit. They agreed that their special representatives on the border issue will meet to explore a fair and reasonable solution, and that Sino-Indian relations are to be stabilized and rebuilt through ministerial-level dialogue mechanisms.

To avoid further twists in the China-India relationship and any malicious geopolitical interference from third parties, both countries should take care to respect their boundary agreements and protocols, drawing on good practices and conflict management experience to clarify the requirements and norms in case of another border crisis. In particular, the scope and mechanism of bilateral cooperation in the border areas should be laid out as plainly as possible.

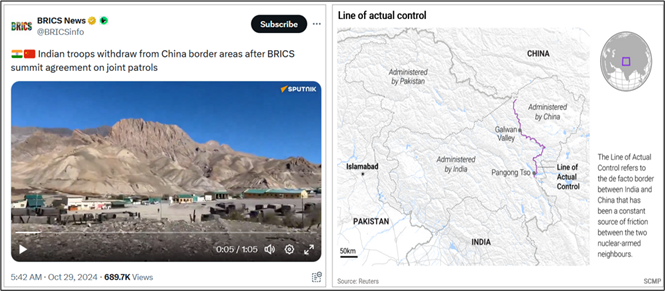

History was made at the BRICS summit in Kazan as China and India formalized a deal to de-escalate along the Himalayan border. Surprisingly soon the results of the BRICS Summit reached the Himalayas. Indian troops were seen leaving areas on the border with China following an agreement on joint patrols reached by the parties.

India-China News | Major Milestone For India-China Ties: Disengagement Progresses Rapidly

NDTV , October 29, 2024

Acces Asia: Are relations between China and India about to thaw? • FRANCE 24 English

FRANCE 24 English , October 25, 2024

Frontier troops of China and India are implementing resolutions over border area issues in an orderly way. At the moment, the Chinese and Indian frontier troops are implementing the resolutions in an orderly way, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian said at a press conference in response to a question regarding the process of disengagement in the India-China border. While analysts highlighted that the disengagement marks an end to the standoff, they emphasized that both countries need to collaborate to restore bilateral ties and India needs to shift focus from geopolitical rivalry and embrace the chance of meaningful cooperation.

India Today reported that Indian and Chinese military commanders are scheduled to meet at the Line of Actual Control (LAC) to confirm the removal of temporary structures and vehicles. Indian Express said that India and China have completed the process of disengagement in two border areas, patrolling will commence soon, talks would continue at the local commanders’ level.

Disengagement is the first step on implementing the resolution, meaning Chinese and Indian troops will no longer confront each other directly at the border. This establishes a buffer zone between the two forces to reduce tensions. The next step may involve further consultations on implementing patrols but the actual implementation may have to wait until spring next year when weather condition is suitable. The disengagement at the two areas will lay the groundwork for negotiations on similar arrangements and portals along the western section of the China-India border and other areas.

Indian troops withdraw from China border areas

Widespread attention

The resolution reached by China and India has drawn widespread attention. US State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said at a press conference that “we’re closely following the developments… We welcome any reduction in tensions along the border.” He also noted that the US has spoken with its Indian partners and been briefed on the matter but did not play any role in the resolution.

US ambassador to India, Eric Garcetti had welcomed the Sino-India deal, stating that “it’s a good day in the Indo-Pacific when any resolution of conflict is reached as in this breakthrough”. However, he also emphasized that the issue of territorial integrity, which India reportedly upheld at the LAC with China, should apply “not just for one part of the world but all parts of the world,” referencing the Ukraine war.

US has long viewed India as a key tool and frontline force to contain China. With fewer border disputes between China and India, the US loses a major leverage to fuel discord between the two nations. However, the gradual resolution of the border issue is clearly in the best interest of both China and India.

China remains committed to viewing India as a development partner and hopes both nations can advance together and share the opportunity for development. Achieving these goals requires joint efforts. Both countries need to collaborate to restore bilateral ties. India should move beyond an outdated Cold War thinking and avoid viewing US-China competition as a strategic opportunity. Instead, it needs to shift focus from geopolitical rivalry and power balancing for meaningful cooperation.

There is reason to believe that both China and India will cherish the valuable solutions, which have gone through four years of twists and turns. The previously well-functioning Special Representatives mechanism on the China-India boundary question will continue to play its role and serve as an important channel for communication on strategic matters between the two nations.

Several Indian media outlets have expressed positive expectations, hoping for cooperation between China and India in areas such as direct passenger flights, electronics manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles, investment, high-level diplomatic interactions, and on the international stage. They also noted that “India’s national interest demands better China ties.” India’s “strategic opportunity period” is most likely to arise from Asian solidarity and the collective progress of the “Global South,” rather than from an assumption of “weakening or replacing China.”

Russia welcomed the recent rapprochement between India and China over their border stand-off following last week’s meeting between Modi and Xi Jinping, while urging that New Delhi should not feel pressured to maintain normal economic relations solely with Western bloc nations.

“It is a positive development in India-China bilateral ties,” Russia’s Ambassador to India, Denis Alipov, told reporters. He also stated that Russia did not play a role in arranging the meeting, but we are happy that it took place in Kazan”. “We wholeheartedly welcome the meeting,” he added.

While Russia and India have traditionally maintained close relations, Moscow’s ties with Beijing have grown steadily stronger following its estrangement from the West.

Fractures in India-US ties, India’s turn from the US to China

India and China agreed to patrol their disputed border area in the way that it was before June 2020’s Galwan River Valley clashes. This was made possible by China finally complying with India’s long-standing request, which in turn paved the way for their leaders to hold a bilateral meeting on the sidelines of this week’s BRICS Summit in Kazan. Obviously, the US was inadvertently responsible for facilitating their deal.

India and China held multiple rounds of talks on their disputed border since 2020, but no breakthrough had occurred until Indo-US ties became characterized by distrust as a result of summer 2023’s scandal and all that followed. It was a case of an alleged Indian assassination attempt against a terrorist-separatist with dual American citizenship on US soil. This episode escalated further covering even Canada this year. This was a turning point in their ties. India-US relations have noticeable soured over this issue.

China realized this rift in India-US relations and took advantage of the opportunity.

China had been reluctant to return to the status quo ante bellum since this was seen as a unilateral concession that could signal weakness and worsen its hand in the South China Sea.The drastic downturn in Indo-US ties, however, led to the aforesaid being perceived as a pragmatic means for managing the abovementioned concerns about India containing China in coordination with the US. The improvement of Sino-Indo ties could therefore place limits on the future improvement of Indo-US ones.

China and India have natural economic complementarities and if the world’s two largest countries ever found a way to unleash their full mutual potential upon resolving their sensitive territorial issues and correspondingly restoring mutual trust, then global affairs would begin to revolve around them. That’s why the US has sought to divide-and-rule them through information warfare and its Kissingerian “triangulation” policy but this failed after it went too far pressuring India over summer 2023’s scandal.

About that, the US never respected India as an equal partner and instead sought to subjugate it as a vassal by demanding that India comply with the West’s unilateral sanctions against Russia, which was unacceptable for both economic and principled reasons. The US also feared India’s rise as a great power, fueled to a large degree by discounted Russian energy, since this accelerated multipolar processes to the detriment of US hegemony.

The meaningful improvement of Sino-Indo relations could lead them closer to unlocking their full mutual potential, which would revolutionize international relations if successful and thus bring an even swifter end to the US’ hegemony.

During the current BRICS session, the most sensational issue with long term consequences actually happened shortly before the summit. India has dropped the US friendly anti-China policies it had implemented during the first two terms of the Modi government. It is (again) making nice with China and Russia while shunning US attempts to make it a sidekick for US policies in Asia.

On the geopolitical front, India has lost significantly during last ten years. It once viewed South Asia and the Indian Ocean as its traditional sphere of influence but after becoming a US ally, none of its neighboring countries remain within its sphere. Instead, India has arguably become more of a subordinate ally to the US.

This was evident, when the US conducted a Freedom of Navigation Operation (FONOPS) in the Indian Ocean on April 7, 2021, which sparked a strong backlash in Indian media and academia, despite India being a US partner. Additionally, the US has been accused of fueling anti-India sentiment in neighboring countries and covertly helping to oust pro-Indian governments in Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives as well as the recent US orchestrated coup in Bangladesh.

This made India realize that the US expects it to relinquish its “strategic autonomy” and that India’s claims to a regional sphere of influence in South Asia are unacceptable to Washington.

Henry Kissinger famously remarked, “It may be dangerous to be America’s enemy, but to be America’s friend is fatal.” This sentiment seems to fit India’s experience perfectly. The US continued to exert political pressure on India at international events.

On the other hand, following the Ukraine war, the West intensified pressure on India to oppose Russia. The US warned India of consequences if it continued to purchase Russian oil and insisted that India abandon its relations with Russia, promising in return to provide arms.

Despite this pressure, India has continued to buy cheap Russian oil and is currently Russia’s largest oil buyer. Russia accounts for approximately 36% of India’s arms imports. The US pressure on India to refrain from purchasing arms and oil from Russia runs counter to India’s national interests.

Ultimately, after four years of experimenting with foreign policy, the Modi government came to understand that China’s cooperation is essential for India’s economic development. The prime minister’s economic adviser argued that China would likely refrain from interfering in India’s border issues due to its dependence on India, coupled with the prospect of increased Chinese investment.

The first and second terms of Modi’s government have marked one of the worst decades in India’s history in regard to international relations. During this period, India has incurred unprecedented opportunity costs while experimenting with international and geopolitical strategies. In his third term, Modi is looking to reverse the course by shifting from the US to China. The piece argues correctly that it was US arrogance towards India which has caused this change.

India’s making nice with China, and its shunning of the U.S., is an immense geopolitical shift. The two biggest countries of this planet by populations plus Russia, the biggest country by landmass, are again friendly to each other. This is a disaster for the US “pivot to Asia” but the western media have barely reported on it.

Broader ramifications in great power relations

China-India border detente paves way for a more balanced world order. While Beijing and New Delhi have their own interests in settling tensions, greater cooperation is a net positive for the Global South.

In a larger geopolitical context, the deal reflects the shaping of a new world order with a non-Western bloc that does not necessarily oppose the West but seeks to challenge its long-held hegemony.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping held their first formal bilateral dialogue in five years on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Kazan. Xi acknowledged the responsibilities of both nations – key members of the Global South – to boost the strength and unity of developing countries. After the meeting, Modi underscored the significance of peace, not just for bilateral ties but for global stability.

India has consistently made it clear that settling the border issue was a necessity for advancing relations with China. Both nations stand to benefit from this development. India seeks to further grow its economy while China needs India to secure vital partnerships amid its economic slump.

China and India have engaged in dialogue for a long time but bilateral tensions have only seemed to increase. Despite these challenges, the BRICS grouping has emerged as a platform for bridging divides, especially with Russia likely to favour more cooperation between China and India.

As BRICS expands its membership, Sino-Indian cooperation is crucial for the grouping’s future, particularly for achieving its strategic goals. These goals are not necessarily anti-Western in nature but part of a broader attempt to build a popular alternative to the West in the world system. Russia also stands to benefit, as having India and China on cordial terms is essential for challenging Western dominance.

India’s recent diplomatic spat with Canada over the Khalistan separatist movement, in which Ottawa was supported by other members of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, seems to have pushed New Delhi further towards working with its non-Western partners.

Given these developments, India has a strong rationale to explore improved ties with China. However, India is likely to keep pursuing its non-alignment policy, maintaining a balanced engagement with the West, particularly Europe. Beijing, meanwhile, has concerns of its own, given New Delhi’s growing relations with Taiwan and its increasing interest in the Tibet autonomous region.

Under Modi’s leadership, India has significantly advanced its technological, economic and diplomatic relations with leaders in Taiwan. Taiwan recently opened its third representative office in India, which sparked a strong rebuke from Beijing. However, India still does not recognize Taiwan as an independent state. With Beijing seeking a peaceful reunification with Taiwan, its interest in resolving the border dispute with India has grown.

While India and China have their own strategic reasons for settling the dispute, Russia also stands to gain from this new-found cooperation. For BRICS to become a credible global counterweight to the West, Moscow needs New Delhi and Beijing to work as cordial partners, if not allies.

Improved Sino-Indian relations could benefit the entire region, especially countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Global South, which stand to gain from reduced tensions between two of Asia’s largest powerhouses.

The 2024 BRICS summit marks the beginning of a new geopolitical reality – one in which India and China constructively manage their differences and contribute to the emergence of a more balanced world order that challenges Western hegemony.

Held in Samoa in the wake of the BRICS Summit in Russia, the 27th Meeting of Heads of State of the Commonwealth of Nations was not attended by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, a demonstration that the prestige of the United Kingdom is on the decline.

India and South Africa sent junior representatives. Parliamentary Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju led the Indian delegation, while Deputy Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Thandi Moraka headed the South African delegation. Modi and Ramaphosa could have attended the Commonwealth meeting instead of the BRICS one. Having preferred to go to Russia denotes a foreign policy decision.

Based on its history, the Commonwealth of Nations is diametrically opposed to BRICS, a group of countries that advocates the creation of a world order based on multipolarity and the development of so-called peripheral countries. Therefore, BRICS is naturally incompatible with the Commonwealth, which represents the idea of the British empire and colonialism.

In effect, the Commonwealth is a meeting around the British Crown to honour and revere its colonial past. Thus, Modi and Ramaphosa’s choice to prioritize the BRICS Summit, to the detriment of the meeting led by King Charles III, reveals the geopolitical reorganization underway worldwide.

The decline of British influence in the world is evident, with countries of the Global South, such as India and South Africa, continuing to question Western policies and practices. These countries advocate some degree of transformation in the international system, mainly in the sphere of economic relations and international institutions, and are becoming far more relevant and important than the UK.

India-Iran Ties: Multidimensional significance of Modi-Pezeshkian meeting

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian meet in Kazan at a time when both India and Iran face pressure from the United States. The October 22 meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian, on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia, was a welcome development, as it was their first meeting and also the first high -level contact between New Delhi and Tehran since the new Iranian government assumed office after the presidential election on July 5.

The Return of the Primakov Triangle

The doctrine takes its name from legendary Yevgeny Primakov, who was appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation by President Boris Yeltsin in 1996. Primakov led the efforts to redirect the foreign policy of Russia away from the West by advocating the formation of a strategic trilateral alliance of Russia, China and India to create a counterbalance to the United States in Eurasia.

The Primakov doctrine revolves around five key ideas: Firstly, Russia is viewed as an indispensable actor who pursues an independent foreign policy; Secondly, Russia ought to pursue a multipolar world managed by a concert of major powers; Thirdly, Russia ought to pursue supremacy in the former Soviet sphere of influence and should pursue Eurasian integration; Fourthly, Russia ought to oppose NATO expansion; Fifthly, Russia should pursue a partnership with China.

The doctrine led to the development of a Russia, India and China trilateral RIC-format, which eventually took shape as a new bloc, the BRICS.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov brought the “Primakov doctrine” term into the geopolitical lexicon as least as early as 2014. He spoke on the eve of Primakov’s 85th birthday, to celebrate the moment Primakov took control of the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Kazan summit proved that the driving force of BRICS is actually the re-invented Primakov Triangle – or RIC (Russia, India, China format). It’s now possible to add Iran and that would make it RIIC. It appears that the entire substance in the inter-connected processes of BRICS integration and Afro-Eurasia integration depends on RIIC.

Closing words

Yevgeny Primakov’s idea of India, Russia and China playing a balancing role in the post-Cold War era was ahead of its time but as recent moves show, it seems to be worth revisiting now.

There are signs that the Russia-India-China platform is becoming “kinetic” after a lapse of a few years. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s official visit to Moscow in June was symbolic too. The visit coincided with NATO’S summit in Washington, which most certainly called attention to the global character of the Russian-Indian relationship in the transformative regional environment in current history.

There were other signposts, too. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s address at the 10th Primakov Readings forum in Moscow on June 26—hardly 10 days before Modi’s visit—was of significance in this connection.

Primakov’s visionary mind came to the conclusion that a Russia-India-China (RIC) format could be of pivotal importance in the emerging post-Cold War world order. Without doubt, Primakov was thinking ahead of his times. At that time neither New Delhi nor Beijing was prepared for such an epochal leap of faith. The heart of the matter is that neither India nor China fully shared Primakov’s revolutionary concept of multipolarity, which was borne out of Russia’s disillusionment with the West.

China possibly could visualize the raison d’être in Primakov’s forecast of the main global development trends for decades ahead. The 1997 Russian-Chinese document titled the Joint Declaration on a Multipolar World and the Establishment of a New International Order hinted at it but India was proceeding other aims.

Now, 25 years later, things have phenomenally changed. The emergence of new centres of power and development outside of the Western world, the pervasive desire to build international relations on broad and equal cooperation, the shift in focus from globalization to regional cooperation—these have become dominant trends. Suffice to say, the time has come for Primakov’s idea that the RIC triangle should become the symbol of the multipolar world and its core.

It may even expand from “Primakov’s triangle” (RIC) to “Primakov’s square” (RIIC). This new format, covering Russia, India, Iran, China (RIIC) would benefit a lot of those “basic initiatives”: Russia’s “Greater Eurasian Partnership” and China’s BRI. No doubt, Russia has a great interest to be a facilitator in relationship of India – Iran – China, as the recent BRICS summit showed in Kazan.