Military capability of China

Defense Forces of the People’s Republic of China

Historical overview 1990-2019

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was initially referred to as the “Red Army” under Mao Zedong. The PLA was not a national institution but rather the military arm of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Established in 1927, the army spent much of its first two decades engaged in fighting the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek during the Chinese Civil War as well as fighting against the Japanese during World War II. In 1949, the PLA expanded to include the PLA Navy (PLAN) and the PLA Air Force (PLAAF). The PLA remained technologically inferior to Western militaries during its early decades but China’s leaders readily employed PLA forces against the United States in Korea and Vietnam.

After Deng Xiaoping’s coming to power in 1978, the path to today’s PLA was set when national defense was included as the fourth of China’s four “modernizations” (the others being industry, science and technology, and agriculture). National defense was accorded the lowest priority, which was seen in military funding and development.

In 1989, PLA units intervened with force on behalf of the CCP to suppress political demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, which considerably damaged the PLA’s domestic and international image. The US military’s performance in the Persian Gulf War provided the PLA stark lessons regarding the lethal effectiveness of information-enabled weapons and forces, which further shook CCP leaders’ confidence in the PLA.

Beijing altered its military doctrine, in the early 1990s:

- from the Mao-era mindset (a war more akin to World War II) to that the most likely conflict China would face would be a “local war under high-technology conditions”.

The PLA’s strategy also changed:

- moving away from the Maoist paradigm of luring an enemy into China to fight a “people’s war” with regular troops.

- instead the PLA began to emphasize a more offensive version of the PLA’s historical strategic concept of “active defense”

- take advantage of longer range, precision-guided munitions (primarily ballistic and cruise missiles) to keep a potential enemy as far as possible from the economically fast-developing Chinese coastal areas by fighting a “noncontact,” short, sharp conflict like the Persian Gulf War

Strategic threat perceptions and other changes

China’s changing strategic threat perceptions also shaped military doctrine and the direction of PLA development:

- the threat of a Soviet invasion disappeared during the 1980s, shifting the focus away from preparing for a World War II– style conflict

- the US 7th Fleet aircraft carrier intervention during the 1996 China-Taiwan “missile crisis” and the accidental NATO strike against China’s Embassy in Serbia in 1999 led Beijing to focus on building capabilities to counter US forces in addition to capabilities to dissuade Taiwan from any political activity Beijing deemed unacceptable.

Entering the 21st century, China’s leaders recognized the confluence of several factors that led them to expand the scope and quicken the pace of PLA development. China’s growing global economic and political interests, rapid technology-driven changes in modern warfare and perceptions of increased strategic-level external threats, including to China’s maritime interests. As a result, throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, China’s leaders initiated several practical steps to modernize the PLA.

- Beijing increased the PLA’s budget by an average of 10 percent per year from 2000 to 2016 and

- established a PLA General Armaments Department in 1998 to rationalize equipment modernization and acquisition processes and

- instituted several broad scientific and technical programs to improve the defense-industrial base and decrease the PLA’s dependence on foreign weapon acquisitions.

In 2004, then-President Hu Jintao outlined for the PLA the “Historic Missions of the Armed Forces in the New Period of the New Century”. These new missions included ensuring China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and domestic security, preserving China’s development, safeguarding China’s expanding national interests and helping ensure world peace.

The PLA’s evolution since President Xi Jinping’s transition to power in 2012 has built on the Hu era but also marked a shift. Xi has focused on strengthening the PLA as a force, underscoring the themes of party rule over the military, improving military capabilities and enhancing the military’s professionalism.

PLA Reform by Xi Jinping

In late 2015, President Xi Jinping unveiled the most substantial PLA reforms in at least 30 years. The reforms were designed to make the PLA a more streamlined force capable of competing with the US military.

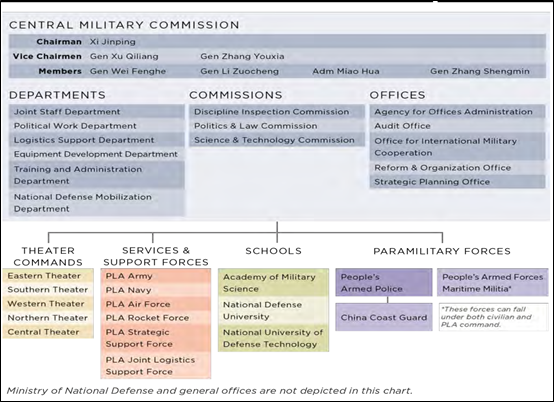

Initial reforms established joint theater commands and a new Joint Staff Department while reorganizing the four general departments that previously ran the PLA into 15 Central Military Commission (CMC) departments and offices. These efforts aimed to clarify command authorities, integrate China’s military services for joint operations and facilitate Beijing’s transition from peace to war.

The structural reforms also established a separate Army headquarters, elevated China’s missile force to a full service by establishing the PLA Rocket Force, unified China’s space and cyber capabilities under the Strategic Support Force and created a Joint Logistics Support Force to direct precision support to PLA operations.

In October 2017, China’s leaders reduced the size of the CMC, shifting toward a more joint command structure in order to streamline strategic decision making, bolster political oversight of the military and build a more integrated and professional force.

In his report to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, Xi Jinping called on the PLA to “prepare for military struggle in all strategic directions,” and said the military was integral to achieving China’s national rejuvenation.

Xi set three developmental benchmarks for the PLA, including becoming a mechanized force with increased informatized and strategic capabilities by 2020, a fully modernized force by 2035, and a worldwide first-class military by midcentury 2050.

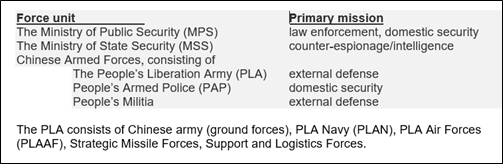

Chinese security apparatus

A variety of Chinese government entities are tasked with domestic security and external defense missions. These forces include:

National security strategy and threat perceptions

Before 2015, departments across the government formulated separate security strategies, but in early 2015, China’s leaders adopted China’s first publicly released national security strategy.

According to the newest White Paper 2019, China’s National Defense in the New Era:

“The Chinese government is issuing China’s National Defense in the New Era to expound on China’s defensive national defense policy and explain the practice, purposes and significance of China’s efforts to build a fortified national defense and a strong military, with a view to helping the international community better understand China’s national defense.”

Global military competition is intensifying and major countries around the world are readjusting their security and military strategies and military organizational structures. They are developing new types of combat forces to seize the strategic commanding heights in military competition, which requires China to speed up the investments and development in military affairs and in national defense.

China’s leaders see China as a country that is “moving closer to center stage” to achieve the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” This ambition permeates China’s national security strategy and the PLA’s role in supporting the party. The CCP remained focused primarily on economic growth throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and in the early 2000s it identified the initial decades of the 21st century as a “period of strategic opportunity” in the international environment that would allow China to focus on building “comprehensive national power.”

The CCP’s contemporary strategic objectives are to:

- Perpetuate CCP rule

- Maintain domestic stability

- Sustain economic growth and development

- Defend national sovereignty and territorial integrity

- Secure China’s status as a great power

The strategy outlines Beijing’s aim to ensure security, promote modernization, as well as preserve China’s socialist system.

Beijing’s view of China’s role in the international community was further elaborated in an article on Xi Jinping’s thoughts on diplomacy published in mid-2017 by one of China’s top diplomats, Yang Jiechi. Yang paints a picture of Chinese diplomacy that focuses on China’s ambition for national rejuvenation and becoming a world power.

Threat perceptions

Beijing’s primary threat perceptions include sovereignty and domestic security issues that it believes could undermine the overriding strategic objective to perpetuate communist rule. These include longstanding concerns regarding Taiwan independence, Uighur and Tibetan separatism and perceived challenges to China’s control of disputed areas in the East and South China Seas.

Authoritative documents also highlight the Korean Peninsula as an area of instability and uncertainty and express concern regarding unsettled territorial disputes along China’s border with India, which periodically result in tense stand-offs like the one that occurred in the summer of 2017 in the disputed Doklam region.

Finally, while the strategy calls for a peer-to-peer cooperative relationship with the United States. China believes that US military presence and US-led security architecture in Asia seeks to constrain China’s rise and interfere with China’s sovereignty, particularly in a Taiwan conflict scenario and in the East and South China Seas. Since the 1990’s, Beijing has repeatedly communicated its preference to move away from the US-led regional security system and has pursued its own regional security initiatives.

Military doctrine and strategy

The party’s perception that China is facing unprecedented security risks is a driving factor in China’s approach to national security. In May 2015, China’s published a document titled China’s Military Strategy (CMS 2015) and White Paper in 2019 (China’s National Defense in the New Era), which outlined how Beijing views the global security environment, China’s role in that environment and how the PLA supports that role. Beijing calculates that world war is unlikely in the immediate future but China should be prepared for the possibility of local war.

Before CMS 2015, there was a series of biennial defense reviews that Beijing published beginning in 1998 to mitigate international concern about the lack of transparency of its military modernization. What differentiated CMS 2015 from its predecessors was that it, for the first time, publicly clarified the PLA’s role in protecting China’s evolving national security interests and shed light on policies, such as the PLA’s commitment to nuclear deterrence.

The report outlined eight “strategic tasks,” or types of missions the PLA must be ready to execute:

- Safeguard the sovereignty of China’s territory

- Safeguard national unification and to oppose and contain “Taiwan independence”

- Safeguard China’s interests in new domains, such as space and cyberspace

- Safeguard China’s overseas interests

- Maintain strategic deterrence

- Participate in international security cooperation

- Maintain China’s political security and social stability

- Conduct emergency rescue, disaster relief, and “rights and interest protection” missions

Beijing views these missions as necessary national security tasks for China to claim great-power status.

China’s leaders for decades have prioritized domestic stability and the continued rule of the CCP. Xi is using the CCP to assert control over all facets of the Chinese state, restricting the space for independent activity across social, political, and economic spheres. China’s armed forces support the CCP’s domestic ambitions without question.

China characterizes its military strategy as one of “active defense,” a concept it describes as strategically defensive but operationally offensive.

President Xi’s speech during the 90th anniversary parade of the PLA further highlighted, that China would never conduct “invasion and expansion” but would never permit “any piece of Chinese territory” to separate from China.

Beijing sees both threats and opportunities emerging from the evolution of the international community beyond the US-led unipolar framework toward a more integrated global environment shaped by major-power dynamics. Furthermore, China sees itself as an emerging major power that will be able to gain influence as long as it can maintain a stable periphery.

China’s military leaders are influential in defense and foreign policy, as the CCP’s armed wing, the PLA is organizationally part of the party apparatus.

Career military officers for the most part are party members and units at the company level and above have political officers responsible for personnel decisions, propaganda and counterintelligence. These political officers are responsible for ensuring that party orders are carried out throughout the PLA. CCP committees, led by the political officers and military commanders, make major decisions in units at all levels.

The CMC, the PLA’s highest decision-making body, is technically both a party organ subordinate to the CCP Central Committee and a governmental office appointed by the National People’s Congress but it is staffed almost exclusively by military officers. The CMC chairman is a civilian who usually serves concurrently as the CCP general secretary and China’s president.

A key driver of ongoing military reforms is Beijing’s desire to increase the PLA’s ability to carry out joint operations on a modern, high-tech battlefield.

PLA’s structures and organizations

The PLA transitionedfrom seven military regions to five “theaters of operations,” or joint commands. This structure is aligned toward Beijing’s perceived “strategic directions,” geographic areas of strategic importance along China’s periphery in which the PLA must be prepared to operate.

The PLA has been and will be a politicized “party army” since its inception and exists to guarantee the CCP regime’s survival above all else, serving the state as a secondary role, in contrast to most Western militaries, which are considered apolitical, professional forces that first and foremost serve the state. Political commissars are responsible for personnel, education, security, discipline, and morale. The Political Work Department, the director of which serves on the CMC, manages the PLA’s political commissars and is the locus for day-to-day political work in the military.

The overall organizational structure of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Chinese military capability in 2019

China’s military goal is to build a strong, combat-effective force capable of winning regional conflicts and employing integrated, real-time command and control networks. In 2018 the PLA published a new “Outline of Military Training and Evaluation” and began to implement revised military training regulations that focused on realistic training for modern warfare and preparations for joint combat operations.

The strategic goals for the development of China’s national defense and military in the new era:

- to generally achieve mechanization by the year 2020 with significantly enhanced informationization and greatly improved strategic capabilities

- to comprehensively advance the modernization of military theory, organizational structure, military personnel, and weaponry and equipment in step with the modernization of the country and basically complete the modernization of national defense and the military by 2035 and

- to fully transform the people’s armed forces into world-class forces by the mid-21st century, 2050

For decades, the foundations of China’s military thinking were based upon Mao’s military thoughts of “people’s war” and later to “local war”, which was envisioned as a short, high-intensity conflict on China’s borders or not far from the border region. CMS 2015 underscores the importance of technological development (RMA).

These RMA-principles can be found in all development work regarding the PLA since CMS 2015. At the same time, Chinese military planners continue to study traditional Chinese sources like Sun Tsu’s “The Art of War” and Mao’s “People’s War”. PLA is in the process of integrating old ideas and emerging modern realities with new concepts and technologies to win the coming wars.

PLA’s new fighting regulations have been published in a book “On Military Campaigns” (Zhanyi Xue), which explains ten Basic Principles of Military Campaigns:

- Know the enemy and know yourself

- Be fully prepared

- Be pro-active

- Concentrate forces

- In-depth strikes

- Take the enemy by surprise

- Unified coordination

- Continuous fighting

- Comprehensive support

- Political superiority

According to Zhanyi Xue, the modern information warfare is a means, not a goal, and shall be used in conjunction with other combat methods to create the conditions for victory. In this context the Chinese term “shashoujian” is important meaning something like “secret weapon or trump card or assassin’s mace; sudden and surprising act”.

The PLA is nowadays active in developing and maintaining international contact network with their counterparts in Asia, Arica and Latin America. China’s armed forces work in defense and security cooperation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and continue to participate in multilateral dialogues and cooperation mechanisms, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Defense Ministers’ Meeting Plus, ASEAN Regional Forum, Shangri-La Dialogue, Jakarta International Defense Dialogue, Western Pacific Naval Symposium and the Xiangshan Forum. China has been very active also in UN peace keeping operations worldwide.

China’s maritime emphasis and concern with protecting its overseas interests have increasingly drawn the PLA beyond China’s borders and immediate periphery. The evolving focus of the PLA Navy (PLAN) from “offshore waters defense” to a mix of offshore waters defense and “open-seas protection”, reflects China’s desire for a wider operational reach. The PLAN has expanded the scope and frequency of extended-range naval deployments, military exercises, and engagements.

One key goal of PLAN’s modernization is perhaps its “greatest ambition”, to acquire a superior “blue water” capability. This is both strategic and symbolic national necessity. This means a strong and powerful navy with plenty of large, domestically designed and built aircraft carriers, in which project the third one is under construction. China’s main priority is to become the peer competitor to the US Pacific Navy.

The establishment of the PLAN’s first overseas military base in Djibouti with a deployed company of Marines and equipment and probable follow-on bases at other locations, signals a turning point in the expansion of PLA operations in the Indian Ocean region and beyond.

These bases and other improvements to the PLA’s ability to project power during the next decade, will increase China’s ability to deter by military force and sustain operations abroad.

In early January 2020, President Xi Jinping signed a mobilization order for the training of the PLA armed forces, the first order of the Central Military Commission (CMC) in 2020. The order stressed strengthening military training in real combat conditions and asked the armed forces to maintain a high level of readiness and step up emergency and combat training.

Power Projection and Expeditionary Operations

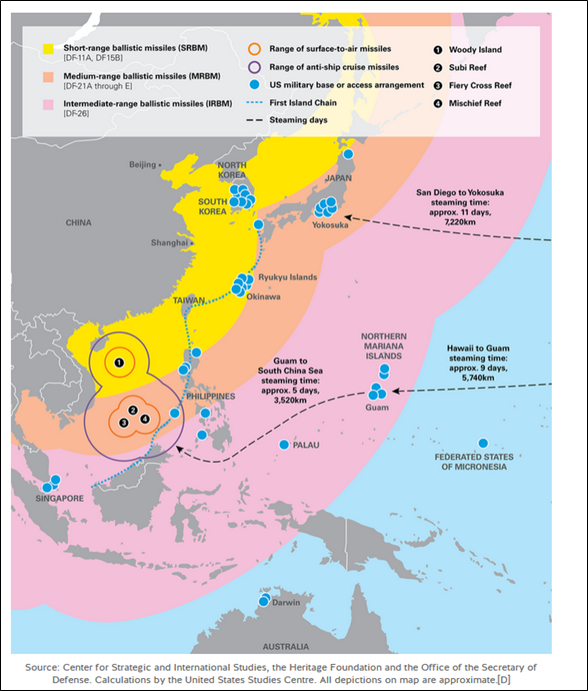

Beijing’s longstanding interest to compel Taiwan’s reunification with the mainland and deter any attempt by Taiwan to declare independence has served as the primary driver for China’s military modernization. Beijing’s anticipation that foreign forces would intervene in a Taiwan scenario led the PLA to develop a range of systems to deter and deny foreign regional force projection. During this modernization process, PLA ground, air, naval and missile forces have become increasingly able to project power during peacetime and in the event of regional conflicts. The PLA has expanded and militarized China’s outposts in the South China Sea, and China’s Coast Guard, backed by the PLAN, commonly harasses Japanese, Philippine and Vietnamese ships in the region.

In this context, China’s threat perception is clear and based on facts in reality, as seen on the following map:

Blue water navy and beyond

China is currently building domestically designed and produced aircraft carriers. The primary purpose of the first domestic aircraft carrier will be to serve a regional defense mission but according to many sources, Beijing’s long-term aim is to become “real blue water navy” projecting power throughout the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean and the whole Pacific. The estimated production plan of military vessels construction by 2030 seems to be convincing.

China’s efforts to enhance its presence abroad, such as establishing its first foreign military base in Djibouti and boosting economic connectivity by BRI and Maritime BRI as well as Arctic BRI, could enable the PLA to project power at even greater distances from the Chinese mainland, although BRI’s are at first hand economic initiatives in Asia, Africa, Europe and now in the Arctic and Latin America, demonstrating the scope of Beijing’s ambition.

Perhaps the most critical feature or vulnerability in the present Chinese military leadership and conduct is the lack of real battle experience, because the Chinese military has not fought a war in 40 years. Therefore, China is enlarging “reality training” both domestically and abroad, especially together with Russia.

Nuclear Forces and Weapons

The nuclear force is a strategic cornerstone for safeguarding national sovereignty and security. China has always pursued the policy of no first use of nuclear weapons and adhered to a self-defensive nuclear strategy. China unconditionally will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or in nuclear-weapons-free zones and will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.

China invests considerable resources to maintain a limited, survivable nuclear force that can guarantee a damaging retaliatory strike. China maintains a stockpile of nuclear warheads and continues research and development and production of new nuclear weapons. Detailed information of China’s nuclear capacity is presented in “Key drivers of military capabilities” on this website.

The China Academy of Engineering Physics—is the key organization in designing, developing and maintaining China’s nuclear force. It employs tens of thousands of personnel and its scientists are capable of conducting all aspects of nuclear weapon design research, including nuclear physics, materials science, electronics, explosives, and computer modeling.

Space / Counterspace / Cyberspace / Artificial Intelligence

The PLA historically has managed China’s space program and continues to invest in improving China’s capabilities in space-based ISR, satellite communication, satellite navigation and meteorology, as well as human space-flight and robotic space exploration.

The PLA’s Strategic Support Force (SSF), established in December 2015, has an important role in the management of China’s aero-space warfare capabilities. Consolidating the PLA’s space, cyber and electronic warfare capabilities into the SSF enables cross-domain synergy in new strategic frontiers.

China continues to develop a variety of counter-space capabilities designed to limit or prevent an adversary’s use of space-based assets during crisis or conflict. In addition to the research and possible development of satellite jammers and directed-energy weapons, China has probably made progress on kinetic energy weapons, including the anti-satellite missile system tested in July 2014. China is employing more sophisticated satellite operations and probably is testing on-orbit dual-use technologies that could be applied to counterspace missions.

The PLA writings identify controlling the “information domain” as a prerequisite for achieving victory in a modern war and as essential for countering outside intervention in a conflict. The information domain encompasses the network, electromagnetic, psychological and intelligence domains corresponding roughly analogous to the current US concept of the cyber domain and cyberwarfare. The PLA Strategic Support Force (SSF) may be the first step in the development of a cyberforce by combining cyber reconnaissance, cyberattack, and cyberdefense capabilities into one organization to reduce bureaucratic hurdles and centralize command and control of PLA cyber units.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is fast heating up as a key area of strategic competition. The Chinese leadership is advancing an “innovation-driven” strategy for civilian and military development, aiming to become the world’s “premier innovation center” in AI by 2030. The PLA anticipates that the advent of AI could fundamentally change the character of warfare, resulting in a transformation from today’s “informatized” ways of warfare to future “intelligentized” warfare, in which AI will be critical to military power.

The PLA is seeking to engage in “leapfrog development” to achieve a decisive edge in “strategic front-line” technologies, in which the United States has not realized and may not be able to achieve a decisive advantage. The PLA is unlikely to pursue a linear trajectory or follow the track of US military modernization but rather could take a different path focusing on the development of “trump card” weapons that seek and target vulnerabilities in the US military.

PLA has pursued research, development and testing for multiple military applications of AI. So far the PLA has succeeded in introducing AI into platforms and systems of its command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities and seeking to advance toward deeper fusion of systems and sensors across all services, theater commands, and domains of warfare.

Chinese military AI and related possible technologies today cover: robotics, autonomously operating guidance and control systems, advanced computing and big data, intelligent unmanned military weapons systems, intelligentized support to command decision-making as well as the expansion of human stamina, skills, and intellect through AI.