Great Powers and power of Covid-19

This overview concentrates on a single viewpoint, that of Covid-19. Later in January 2021, a new blog is coming regarding the postures of great powers in the triangle game.

It is far from clear how the world will eventually transition from the current Covid-19 pandemic towards a possibly (?) better future. The economic devastation from the pandemic is global in scope but Western economies seem particularly hardest hit. The United States and Europe are grimly looking at abysmal falls in their economies which are being described as the worst since the Great Depression during the 1930s. There is little doubt that the pandemic is bringing about large changes in the world. This is the geopolitical second wave and its power ramifications, which are already starting to concern Western leaders.

“Historians love chapter breaks,” has Robert Kaplan said, an American foreign-policy expert and former member of the US Defense Policy Board, “Covid-19 will come to be seen as a chapter break.”

Some statistics as a starter

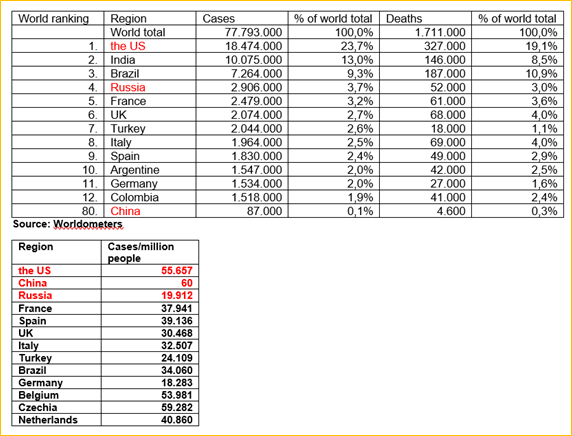

When analyzing the incidence of Covid-19 among great powers, some interesting statistical figures can be wrap up, figures below in late December 2020.

(Source: Worldometers)

The “original virus source”, China, seems to succeeded by far the best and even Russia has managed to curb the pandemic moderately well relatively, compared with many big Western European countries.

In the US, President Trump has been generating chaos and incoherence assaulting upon science and US public health institutions and politicizing the pandemic response. As a consequence, the scale, scope, and velocity of the US outbreak far outstrips Russia’s, China’s and the rest of the world’s, as does the staggering loss of life. The US prestige and influence have suffered a lot. The United States has entered a world of trouble far beyond anything Russia or China faces today.

The President-elect Biden will face an inheritance of unprecedented malfeasance, an uncontrolled, sweeping pandemic, unthinkable numbers of Americans dead and a visible decline of global prestige and trust. Recovery and repair will require far more effort, for far longer, than is commonly realized. The United States’ place in the world cannot be fixed simply by restoring WHO membership and apology for recent decisions. This may be for the first time in the post-war history, the rest of the world views the United States not with respect but pity.

Perfect storm…or vaccine relief

The modern world may face a “perfect storm”: The combination of a deadly and highly infectious virus, an emerging worldwide economic depression, the collapse of global governance and an absence of a coordinated and effective international response. How this storm will end remains unknown, eventually a satisfactory remedy will emerge through some combination of vaccines, improved treatment methods, social distancing and new mechanisms of international trade. In a globally connected world with increasingly interdependent economies and an unprecedented high-speed flow of both people and goods across the world, it did not require an excessive imagination to foresee the risk of a future pandemic.

At the same time, the general approach of governments around the world of narrowly defining their priorities created a climate and context in which the virus emerged and in which necessary precautions were ignored. Ending the pandemic requires effective responses, both individual and collective, from key political and economic powers such as the United States, China, Japan, the European Union, Russia, Great Britain and France.

One lesson to be learned is the primacy of sovereign states. It is obvious that the pandemic is prompting governments to focus on their national interests first. Only on that basis can they then seek to engage in international cooperation. However, the governments of the great powers should acknowledge their collective culpability for failing to identify global priorities and instead taking imprudent steps that diverted attention from issues of major global concern in favor of non-essential local issues.

Like most countries, the United States tended to address immediate challenges that had receptive audiences at home. Domestic problems also crowded out any space for action on this issue. The world’s most powerful nations began thinking not in terms of their fundamental national priorities but rather, how they could maximize their immediate competitive advantages. Institutions like the UN, World Trade Organization, and World Health Organization (WHO) are not a panacea for world ills but they can provide useful, if limited, signals ahead of trouble and serve as shock absorbers for international disagreements. Particularly, the US skipped them away.

While there are hopeful signs coming from China and elsewhere that social distancing and carefully designed quarantines can work, the time and the economic and human sacrifice needed for these measures to end the crisis are impossible to predict.

Chinese perspective

In spring 2020, amid the deepest economic contraction in nearly a century, President Xi Jinping made it very clear that China should be ready for unprecedented, relentless foreign challenges. He was not only referring to the possible widening China-US trade tension or the non-stop demonization of every project related to the Belt and Road Initiative.

According to highly classified Chinese document, leaked by some Western-connected source and excerpts published by Reuters in May 2020, China would have to “prepare for armed confrontation between the two global powers” (a reference to the US). Now the whole game is about hybrid warfare 2.0 deployed by the US to contain the emerging superpower China whatever it takes and this report was an aggressive strategy reply deployed by the Chinese state. This topic will be later examined closely in coming blogs on this website.

The Chinese character for “crisis” famously carries a second meaning “opportunity.” Although the world currently finds itself in the center of an existential crisis, a promising opportunity may well rest just over the horizon.

European perspective.

A recent analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit predicts that the geopolitical balance of economic power will pivot decisively from West to East following the pandemic. The EIU comments: “It will act as an accelerant of existing geopolitical trends, in particular the growing rivalry between the US and China and the shift in the economic balance of power from West to East.”

The failure to mobilize a pan-European response to the crisis and the tendency of member states to look after their own citizens has dealt a blow to the EU: member states did not act in concert when the crisis erupted in Europe, but unilaterally, closing borders, suspending free movement and stopping transport links without co-ordination.

The lack of pan-European solidarity was striking, as Italy’s appeal for assistance was initially ignored by other European states, allowing China to step in to offer help and therefore bolster its global influence. As the crisis spread across the continent, festering divisions within the bloc between North and South, East and West and so on, came to the fore. Coming after the sovereign debt crisis, the migrant crisis and Brexit, the coronavirus crisis will further damage the EU. In late 2020 EU seems finally managing some coherent and coordinated measures to be done.

Regional powers such as Turkey, Iran and others have in recent years sought to capitalize on the increasing fragmentation of the global order by asserting leadership in their backyards.

Geopolitics after Covid-19: is the pandemic a turning point?

The coronavirus pandemic is not steering in a new global order but it will change things, at least in three important ways:

It will bring to the surface such developments that had previously gone largely unnoticed.

It will act as an accelerant of existing geopolitical trends, in particular the growing rivalry between the US and China and the shift in the economic balance of power from West to East.

It will be a catalyst for changes that are presently difficult to predict, in both the developed and developing world, from the future of the EU to the role of other powers.

In times of crisis, global rivalries tend to intensify rather than abate. The coronavirus crisis has led to a further deterioration in the already chronically bad relations between China and the US. As things stand, there seems little prospect that the damage can be repaired in the short term. The expansion of the coronavirus spread outside China and around the world has led to a disinformation war. In the battle to influence international public opinion, China has also been contrasting its “efficiency” in containing the virus with the way the pandemic has been “mishandled” by Western democratic states such as the US.

The pandemic will accelerate the shift in the global balance of power from the West to the East. The negative effect of the pandemic on the mature, developed economies of Europe and the US may be long-lasting. The extraordinary fiscal and monetary measures that these countries are taking to support businesses and households will be hard to reverse. There is a risk raising the chances of sovereign debt crises in developed economies in the medium term. The pandemic will accelerate the fragmentation and re-composition of the global world order, to the benefit of emerging powers such as China and Russia and potentially also such regional powers like Turkey and Iran.

China is likely to emerge from the crisis as a bigger global player. China is trying hard to repair the reputational damage caused by its initial bungling of the coronavirus outbreak, in particular by sharing medical expertise, sending aid and filling some medical supply shortages around the world. Relations with the US, in particular, and with western Europe will become more difficult. However, it seems highly likely that the crisis will crystallize the development of clearly demarcated Chinese spheres of influence in parts of Africa, eastern Europe, Latin America and South-east Asia. China now has an opportunity to expand its influence by providing expertise and support to countries hard hit by the pandemic.

The “America First” policy of Donald Trump had arguably already led to a diminution of US power globally, as many countries increasingly feel that the US is not a reliable, trustworthy partner. However, the US’s retreat from the world stage has given China an opportunity to fill certain vacuums, particularly as the epidemic has forced the US to turn inwards for now. It would be a mistake, however, to underestimate the power and leadership of the US, which is certainly aware of China’s intentions and is likely to fight back.

As evolutionary epidemiologist Rob Wallace eloquently put it in his recent interview: “Pandemics are mirrors. They tell a society its status.”

The escalation of provocative accusations from the Trump administration against China blaming the latter for the pandemic are obviously baseless. The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified American hostility towards Beijing precisely because the crisis has exposed the frailty of US global power and the underlying shift that was already underway away from a US-dominated world order.

In a world confronted by existential threats, the emphasis must be on multilateral cooperation and mutual partnership. The story of an invisible pathogen moving swiftly and seamlessly across borders, rendering trillion-dollar security systems futile, demonstrates the imperative of global cooperation.

The US foreign policy “America First” and more generally “American unipolar self-righteousness” has proved as dangerous fallacies. With extraordinarily high death tolls, the US and UK demonstrate their socio-economic systems are far from a healthy status, in this context the Anglo-American societal model seems to be a failure.

China and Eurasia more generally appear to have shown greater fortitude and resilience in managing the pandemic. The death tolls are much less compared with Western nations, despite widespread infection from Covid-19. Part of that success is stronger state intervention and public health services. This is not to claim that China, Russia and other Eurasian states are models of economic progress to be emulated by the rest of the world but one thing may be the consistent advocacy of multilateralism and mutual partnership which leaders of these countries have made over many years.

As Henry Kissinger recently expressed in the Wall Street Journal, “No country, not even the US, can in a purely national effort overcome the virus. Addressing the necessities of the moment must ultimately be coupled with a global collaborative vision and program. If we cannot do both in tandem, we will face the worst of each.”

The US after November 2020 elections

Presidential election campaigns in the US usually have a detrimental impact on the consistency of US foreign policy, due to domestic partisan clashes. The incumbent president seeking reelection has to demonstrate to the electorate that he is strong, tough and decisive in dealing with foreign partners and, especially, with foreign adversaries.

The American political culture has never been particularly apt dealing with foreign adversaries as peers. Any radical shift of the US approach to China after the November elections is not very likely. The same can be assessed regarding Russia – the US relations. The frozen relations of present great powers will prevail far in the future. The American economic situation seems to be as fuzzy as the coming foreign policy.